|

Claire Tizzard, Carleton University Graduate  London, Ontario. October, 2020 London, Ontario. October, 2020 The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we think about a lot of things including the way we travel, how we shop, and even where we live. Early on, as the pandemic containment measures were announced, it seemed that those who could were trading in their urban lives for the peace and tranquility of their rural cottages. Inspired, perhaps, by the wish to escape the higher transmission rates in urban centers but also the increasingly strict restrictions on public space. Those who longed for nature were encouraged to seek rural areas and homes with private backyard space in place of their urban apartments. Given that this is not an accessible option for most people, the role of urban development in the promotion of resilience and well-being has been brought into sharp focus. The thought of urban development might elicit images in our minds of new apartment buildings with large windows and rooftop patios, and while this is not the extent of urban development, it does make up an important part. The architectural features of our living space contribute to our mental health and wellbeing, particularly when we face restrictions on our ability to leave these spaces. The loss of daily routine, social gatherings, and the amalgamation of home and workspace have had a significant impact on mental health and wellbeing, all of which are compounded for those in densely packed urban areas.  A study conducted in Northern Italy, a region that experienced severe lockdown restrictions due to COVID-19, looked at the impact of features of built living spaces on university students found that living in small apartments, lacking a functional balcony, and having a poor view were each associated with moderate to severe depression symptoms (1). These living features are not uncommon as we experience a global trend of movement to urban centers where space is limited. To combat these negative psychological effects, people took to parks and local greenspace. A study that analyzed data from the Google Community Mobility Report found an increase in park visitation from February to May 2020, by over 100%, compared to the same time period the previous year, in Canada, Denmark, and the United Kingdom. Similar increases were found in Spain and Italy once the most strictest lockdown restrictions were lifted (2).  Time outdoors appears to be an important coping strategy. Nature provides an escape from confined living quarters and a time of relaxation to release the stress and anxiety felt most acutely by those in urban centers. Urban greenspaces are not only places to enjoy nature and physical activity but are also places to enjoy social connection. Community gardens and parks help foster social ties that can be maintained safely during social distancing measures to further reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness and foster resilience in a community. A survey of Tokyo residents explored the relationship between mental health scores, outdoor experience, and lifestyle factors to further understand their interaction amidst the increased psychological stress of the coronavirus pandemic. They found that greenspace use and view were both individually associated with higher life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem scores. Greenspace use and view were also both independently associated with lower loneliness, depression and anxiety scores (3). This supports the importance of greenspace in maintaining our mental health and wellbeing through periods of significant stress. However, greenspace is not equally accessible. Data from the Google Community Report found that park visitation and access were correlated with economic, cultural, and social dimensions. Higher socio-economic status communities experienced greater park access and visitation rates, while poverty and unemployment were correlated with reduced park access and visitation (2). Wealthier areas tend to have a greater diversity of species, higher tree cover, and are therefore, less susceptible to environmental changes (4). This inequality in greenspace access could compound the negative effects felt by disadvantaged populations due to COVID-19. Recognizing these data is important in our understanding of the impact of urban development on our wellbeing, especially as we prepare for future pandemics where quarantine measures may again be necessary for preliminary containment. Architectural design should include consideration of living features that have been found to be correlated with positive mental health and wellbeing such as a livable balcony, increased natural lighting, and larger and more functional space, all of which are a function of access to resources and socio-economic status. In addition, urban nature protection and development should be a priority as they have been shown to protect mental wellbeing and foster resilience in communities. Focus should also be brought to increasing equity in the distribution of urban nature development to benefit lower socio-economic communities who are at an increased risk of experiencing negative impacts to wellbeing.  The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we think about a lot of things, including how we appreciate urban greenspaces. They are no longer simply spaces that we enjoy individually, but have become crucial to maintaining our mental health and wellbeing. Urban greenspaces are places for physical activity, stress relief, and community interaction, all of which are key to combatting feelings of loneliness and isolation during lockdown restrictions. As we prepare for future pandemics, urban development that prioritizes greenspace is fundamental to fostering resilience in those who live in urban centers. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

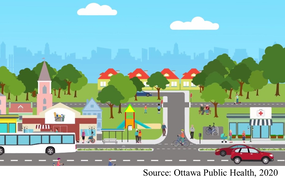

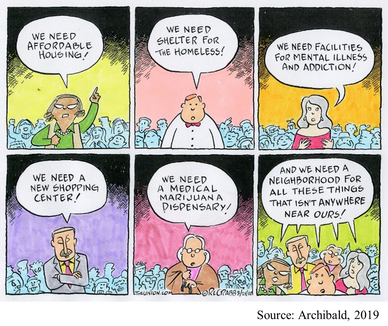

Hilary Ziraldo, Carleton University Student On the day I wrote this, exactly one year had passed since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Like every other day that year, I was at my home in Toronto, only leaving to get groceries or to exercise outside. When I ran into my mom as she headed down the stairs to her basement work-from-home setup, she liked to joke that there was “heavy traffic” on her morning commute. Joking aside, COVID-19 has changed how we interact with our physical environments. We have become increasingly dependent on our homes and neighbourhoods to support our physical and mental health needs, and this has intensified health disparities between those living in adequate and inadequate conditions. The impacts of housing on health are numerous. Overcrowding can increase the spread of communicable infections, while chronic diseases, such as asthma, are associated with substandard heating, insulation and dampness (1,2). Unsafe or unaffordable housing is also a source of chronic stress and can lead to social isolation and poor mental health (2,3,4). Despite these broad consequences, 15.3% of Ontario households live in unsuitable, inadequate or unaffordable conditions, and affordable housing has been consistently de-prioritized by the provincial government (5). I find this alarming because housing is an essential human right, yet continues to be treated as non-essential by government decision-makers and the voting public. Due the high rates of poor-quality and unaffordable housing in Ontario, stay at home orders during the COVID-19 pandemic confined many Ontarians to unhealthy living conditions. Essential workers are also impacted because income is a determinant of housing quality, and the reality is that many frontline jobs are poorly compensated (6). For essential workers living in crowded or intergenerational households, continuing to work puts themselves and their families at greater risk due to both workplace exposures and their household conditions. Beyond housing, our neighbourhoods can have a large impact on health. Residents are more likely to be physically active in safe, walkable neighbourhoods and to choose healthy foods when they are easily accessible (7,8). In neighbourhoods designed to facilitate gatherings, residents perceive greater social support and a stronger sense of community belonging (8). Due to the impact of neighbourhood features on health, vast disparities in health may occur between otherwise geographically close communities. Like quality of housing, quality of neighbourhoods is largely determined by income (6) and this cannot be fixed by simply investing in the development of low-income neighbourhoods. When lower income neighbourhoods are revitalized, gentrification may occur. Gentrification refers to the transformation of the social, economic, cultural, physical and demographic features of a neighbourhood, and often leads to the displacement of long-term and socially marginalized residents (9). In a neighbourhood impacted by gentrification, property and rental values are inflated, pushing vulnerable populations to relocate.  However, there are ways to break the cycle of revitalization and displacement caused by gentrification. The City of Ottawa is incorporating public health concepts into urban growth strategies by creating ‘15-minute neighbourhoods’ (10). A 15-minute neighbourhood is one in which all (or most) daily needs can be accessed within a 15-minute walk from one’s home. The goal of a 15-minute neighbourhood is to reduce reliance on vehicles, increase social connections, and promote equity through improved access to daily needs (10). At the provincial level, Ontario has tried to combat income-based disparities in access to healthy built environments through inclusionary zoning regulations (11). Inclusionary zoning is a strategy to increase affordable housing in desirable neighbourhoods. Under an inclusionary zoning system, every new housing development must be mixed income, meaning that a range of income levels can afford to live in high-quality housing within updated neighbourhoods. Inclusionary zoning has shown some success in the United States, but there is concern that provincial actions will be ineffective at the municipal level. Under the current system, the power to enforce inclusionary zoning lies with municipal governments, that will need to implement bylaws and regulations surrounding the construction of affordable housing units (12). By leaving decisions on inclusionary zoning to municipalities, substantial changes are not guaranteed.  When we understand the magnitude of Ontario’s housing crisis, it is easy to support policy action, like inclusionary zoning. But, take a moment to consider your perspective if affordable housing was proposed in your own neighbourhood? As is too often the case, such a policy might be easy to support until you are personally affected. For residents living near areas allocated for affordable housing, the “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) phenomenon is both common and predictable. The NIMBY phenomenon refers to the opposition of new developments by residents when they believe the development will negatively impact their neighbourhood or property value. Classical examples of the NIMBY phenomenon include responses to safe injection sites and homeless shelters, but affordable housing is similarly affected (13). NIMBY responses are often founded in stereotypes and stigma and serve to perpetuate social inequities. One method governments and developers can use to fight the NIMBY phenomenon is to engage and inform residents throughout the planning process. Importantly, we can individually work against NIMBY-ism by discussing the value of diverse communities with family, friends, and neighbours and being leaders for social equity within our own neighbourhoods. As I sat at my desk in Toronto with the entire province under stay at home orders, I couldn’t help but appreciate how much I relied on my home and neighbourhood over the past year. But, for many Ontarians, hiding away at home has not been a refuge from the dangers of COVID-19. Improving access to healthy homes and neighbourhoods is a complex battle involving political priorities, revitalization and gentrification, and local sentiments. As we move forwards in the COVID-19 pandemic and into its aftermath, we must do more to ensure that “home” is a healthy environment for all Ontarians. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

Katie Vick, Carleton University Student Introduction A common concern expressed by many people throughout the pandemic has been the fear of weight gain from being cooped up inside. Gyms are closed, banana bread recipes are trending, and the weight gain of the coined ‘Quarantine 15’ is on folks’ minds (1,2). Recent research reports negative changes in diet, exercise, and body image worldwide since the pandemic began (3,4,5,6). While one might expect body image comparisons to dissipate with social distancing, this has not been the case. To the contrary, these unprecedented times have forged new opportunities for body image concerns to creep into our consciousness - perhaps in more pervasive ways than before. Social Media Up to 80% of people report spending more time on social media during the pandemic, and this had no doubt been helpful to connect people during isolation,. However, there has been a concurrent shift in the tone of social media content. On the one hand, there is a greater frequency of posts about exercise and diet, and a prevalence of blatantly weight-stigmatizing and fat-phobic body image memes and comparisons, and so it is no surprise that body image issues are rising (7,8). On the other hand, the increased exposure to unrealistic presentations of happiness, accomplishment and appearance can also be harmful. These idealistic posts can prompt social comparisons that are associated with poor self-esteem. I began to notice myself making these comparisons during my morning scroll: Everyone was exercising and eating well… Was I supposed to make my banana bread and eat it too? From what I could tell, everyone on Instagram had their quarantine routine together except for me. Influencers are not only individual sources posting about personal weight-gain concerns. Some nations, such as England, have made it a part of their public health strategy to promote healthy eating and exercise routines throughout lockdown. While well-intentioned, these posts can be harmful to people vulnerable to body image concerns (7,9). When even the government is telling you to do more despite doing everything that you can to just stay sane (which, for some of us, means to avoid compulsively worrying about the number on the scale), it is easy to feel like you aren’t doing enough to be a health goddess.  Video Conferences One study found that video conferencing also affected body satisfaction. Many workplaces have been relying on video conferencing tools during social distancing. We are forced to look at ourselves through others' eyes during video calls much more than we otherwise would. I don’t know about you but having a virtual mirror for three hours of my day is less than ideal, especially when my girlfriends always seem to have their hair and makeup on point in every. single. zoom. call. We usually see our faces directly beside others in the meeting, creating opportunities for direct comparisons (often with many people at once) and self-criticism. Women’s tendency to pay more attention to appearance means that they might be engaging in these comparisons more often, contributing to greater zoom fatigue amongst women compared to men (10). In response, some people have started to use filters to improve their appearance. Using filters can be detrimental by creating unachievable beauty standards, intensifying the problem (11,12). Women have generally reported poorer mental health than men during the pandemic, and this effect exists with body dissatisfaction (13,9). Women reported being more bothered than men by changes in appetite in response to lockdown stress. This might be because women are exposed to more weight-stigmatizing social media messaging. Women also tend to engage in more 'fat talk' or discussions about their pandemic-related weight concerns. I find this particularly interesting with my coworkers, as I have never seen many of their faces due to masking procedures; we have these conversations without even knowing what the other person looks like!  What Now? Experts say that these effects are part of our diet culture (1,2). While the memes might make us feel connected or lift our spirits, they also reinforce the idea of 'good' and 'bad' foods, body shapes and behaviours. The science is clear that weight gain, especially during times of stress (e.g., a global pandemic?!?!) is very complicated. However, social media posts about ‘thinspo,' fad diets, and exercise to avoid lockdown-related weight gain often associate extra pounds with being lazy or unmotivated. This false information can be very stressful. Some people are noticing the return or escalation of unhealthy thoughts and behaviours (9,14,15). Research has found that relationships with food have become more negative throughout the lockdowns, with people restricting and bingeing more than they did pre-pandemic (7,5,6). Some people have reported anxiety about being unable to exercise or to buy guilt-free foods during gym closures and food scarcity (7,6). Due to the unpredictability of lockdowns, for many, what they eat is a form of control (16). With social distancing, there is also little accountability. Friends have confided to me that a ‘lack of supervision’ enabled them to restart unhealthy patterns. Fortunately, some are reaching out, with professionals who were interviewed in Calgary reporting an increased demand for eating disorder supports. In conclusion, the isolation and stress experienced during the COVID-19 lockdowns are hurting our relationships with food and bodies as we spend more time alone and in the digital sphere. We need to continue to pay attention to our loved ones' wellbeing, especially those are predisposed to body image issues, or who have a history of disordered eating. We need to change how we respond to ourselves and others. Instead of validating a friend’s weight concerns, challenge them to be critical of diet culture, identify ways that their bodies feel strong, and acknowledge that their body is doing what it can to keep them healthy and functional in a challenging time. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

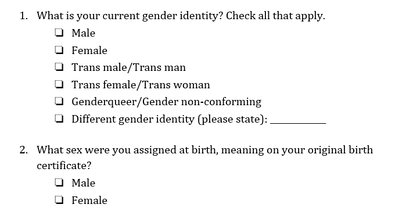

Genderqueer Pride Flag Genderqueer Pride Flag Jaya Rastogi, Health Science, Technology, and Policy MSc Student “For me, going to the doctor is scary and dangerous,” said a genderqueer undergraduate student accessing healthcare in Ontario. “I called my family doctor to ask about [a health service that is unique for genderqueer individuals]. He said ‘I’ve never heard of that. What is that? I don’t know how to do that.’ This says to me that my doctor hasn’t educated himself enough, which seems irresponsible.” The genderqueer and trans community Genderqueer and trans individuals face unique barriers when accessing health care. In 2018, Carleton University’s independent newspaper, the Charlatan, reported on an Algonquin College student, Ashton Schofield, who faced multiple challenges accessing trans-inclusive healthcare in Ottawa. He faced numerous barriers to care including limited providers with enough knowledge to treat trans patients, long wait times for the limited providers, and an incorrect hormone medication prescription (1). Schofield’s story is not unique. As many as 1 in 200 Ontarians are trans and 11% of LGBTQ+ youth are genderqueer/gender nonconforming (2,3). Like Schofield, both genderqueer and trans individuals often face challenges accessing healthcare (4). Genderqueer is a term used to describe an individual who does not conform to one of the two binary genders⁵. Trans is an umbrella term used to describe people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth (5,6). Some genderqueer individuals identify as trans, while others do not (7). Barriers to access and exclusion from healthcare Genderqueer and trans communities face several barriers to accessing trans-inclusive healthcare in Canada, including a lack of relevant and easily available information, self-esteem and mental health issues, challenges finding help, and ongoing experiences of transphobia (8,9). Genderqueer individuals face health-related challenges at even higher rates than binary trans people, including avoiding care due to a fear of discrimination and providers refusing to treat them (10). Genderqueer young people are becoming increasingly visible in healthcare and our communities but are paid little attention when it comes to their unique healthcare needs (9). Trans and genderqueer Canadians also experience social exclusion from healthcare (8). Many medical clinics only have male and female washrooms (11), which communicates to genderqueer individuals that their identity is not welcome in the space. Medical intake forms typically ask patients to select their sex and provide the options of male and female without asking about gender or providing any space for further elaboration (11). This says to genderqueer individuals that their identity is not acknowledged or respected in the health system. Commenting about health intake forms, the genderqueer youth quoted earlier said, “the last medical form I filled out was a form for a blood test and the options were male and female. Since I’m genderqueer I think female and male are just two really small categories.” They continued, “it’s very hard for others to respect me being androgynous. Being genderqueer is the most freeing thing because I’m not confined to these little boxes of sex or gender. Scientists and doctors are supposed to help me, but they’re the ones confining me to these little boxes. They’ll say, ‘you have to pick one or we’re going to pick for you.’ ”  Improving health intake forms Health forms are not set in stone and should be improved to better serve the genderqueer and trans community. Improving health forms is an important step in breaking down barriers to care for genderqueer and trans individuals. A recent Ontario Medical Association (OMA) report (2020) highlighted that a number of factors can lead trans youth to avoid health care (13), including the system’s focus on the gender binary and medical intake forms that ask only if a patient is male or female. A majority of trans youth criticized medical forms for being very male/female centered in a recent Manitoba-based study on trans youth’s experience in the healthcare system (12). Improving health forms would generate accurate data and provide visibility to the genderqueer and trans community. Demonstrating that genderqueer and trans people exist in local hospitals, medical clinics, and communities is important when advocating for inclusive policy, inclusive program creation and funding, and other resource allocation (12,14). The 2-step method for asking sex and gender One tool to improve visibility and accessibility in healthcare is the 2-step method for asking sex and gender, which was developed by the Gender Identity in U.S. Surveillance Group (14). This 2-step method would replace the current 1-step method that only asks a person’s sex and offers male or female as the only response options. In the 2-step method, individuals would be able to differentiate between their sex assigned at birth and their current gender identity while also having multiple options to select for current gender identity. See below for 2-step sex and gender questions (7):  Progress Pride Flag Progress Pride Flag This 2-step method was originally created for surveys but is also recommended for use in health intake forms (15). Recent Canadian research found that the 2-step method captures genderqueer and trans people’s identities better than the 1-step method, validates these identities, and was not confusing to people who are not trans (also called cis) (7). However, the 2-step method was not sufficient for some Indigenous people, and other response options may need to be added to the questions, such as two-spirit (7). There is not enough research to understand if intersex people find that the 2-step method correctly captures their identities (7). Intersex refers to individuals whose hormones or chromosomes create characteristics that are not consistently male or female (7). Additionally, some scholars argue that sex and gender markers should be eliminated wherever they are not necessary (2). While more work needs to be done to ensure questions about sex and gender accurately capture genderqueer and trans peoples’ identities, implementing the 2-step method in health intake forms is a promising step towards making healthcare more accurate and validating for trans and genderqueer individuals.

|

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed