|

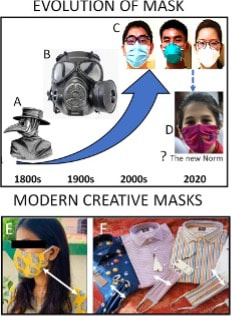

By Emily Tippins, Carleton Graduate Student Face masks have been a predominant symbol of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, mask mandates and mandates in general have been—and continue to be—quite divisive. With conflicting political and scientific messaging about the virus, many individuals are left unsure about the science behind masking and if they should continue to be worn to protect their health and the health of others. Previous studies have speculated that culture plays a fundamental role in shaping people’s response and subsequent health behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Biddlestone et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021). It has become increasingly apparent that behavioural science is essential for understanding and addressing the decisions on whether to refuse or adhere to health guidelines, as well as the influential role that cultural perspectives and political messaging have on these behaviours.  Historically, face masks have played an important role in protecting against the spread of infection (Bakshi et al., 2021). Masks were first aimed to stop bad smells until the 1700s when their medical functions became known. The “miasmatic” theory of disease hypothesized that most diseases were caused by inhaling a “miasma,” thought to be infected air through exposure to corpses and the exhalations of infected individuals (Halliday, 2001). As developments in the field of microbiology were made during the 1800s, miasmatic theory was disproved, and the mask began to transform from the iconic bird-beak masks (see Figure 1; mask A) which were filled with herbal materials thought to keep off the plague, to be more suitable to healthcare needs (see Figure 1; mask C; Lynteris, 2018). As health risks associated with asbestos inhalation became apparent and the risk of the inhalation of toxic dust was identified among mining and construction workers, recommendations were put in place to use masks in workplaces where exposure to harmful chemicals occurs (Goh et al., 2020). Presently, medical technology has advanced, and a large variety of face masks have been developed, many of which are being used by the general population for protection against COVID-19. However, even with the variety of masks available, the data is still unclear on how well they work or when to use them. Earlier this year, a Cochrane review was published suggesting that face masks don’t work in community settings. However, many experts criticized this review’s methodology and assumptions regarding infection transmission and warned that the conclusions are misleading. Contentious political discourse discrediting and discouraging the use of face masks has added to the confusion and decreased public adherence to this protective health behaviour around the world (Bakshi et al., 2021). One identified reason for the lack of compelling evidence on the efficacy of public mask wearing is the lack of controlled trials due to logistical and ethical reasons during the pandemic (Ju et al., 2021). Furthermore, it is thought that the primary route of transmission of COVID-19 is via respiratory particles; however, even this notion has been criticized. A systematic review sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that mask-wearing reduces transmissibility per contact by reducing transmission of infected respiratory particles (Chu et al., 2020). However, the amount of protection you receive from a mask depends on the quality of the mask and how well it fits. Thankfully, guidance from reputable sources like the Public Health Agency of Canada and the WHO have resources on proper COVID-19 mask use. Despite these available resources, many individuals still choose to not wear a mask in public spaces.  We now understand that face masks are most effective when 100% of the individuals in a public space are wearing one (Chu et al., 2020). Therefore, in order for protective face masks (in conjunction with other preventive health measures) to mitigate the transmission of COVID-19, they must be viewed as the standard acceptable behaviour by the general public in order to adopt and maintain this social norm (Bokemper et al., 2021). Research has shown that culture fundamentally shapes how people respond to crises like the COVID-19 pandemic (see Lu et al., 2021). It has also been found that collectivist cultures demonstrate greater adherence to social norms (see Tripathi & Leviatan, 2003). Collectivism encapsulates the tendency to be more concerned with the group’s needs, goals, and interests than with individualistic-oriented interests (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). It has been speculated that a sense of collectivism may improve individuals’ attitudes toward behaviours that involve personal discomfort, such as masking. Places with cultures that are considered to be more collectivist (e.g., Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea) contained the spread of COVID-19 more effectively than places with more individualist cultures (e.g., United States, Spain, and Italy; Biddlestone et al., 2020). Unfortunately, people in individualist cultures often prioritize their personal convenience or preference while ignoring the collective consequences of doing so. For example, although properly fitted masks effectively protect against COVID-19, they can be uncomfortable and create inconvenience. Thus, more community-minded thinking that aligns with collectivist cultural norms would need to be adopted in order to encourage mask-wearing in public settings.  Leadership is critical in adopting collectivist cultural norms (Lu et al., 2021). Unfortunately, the politicization of masks has led some individuals to not fully adopt masking due to political polarization. In fact, some report that choosing to wear a mask may be seen as making a political statement. Policy recommendations and the public acceptability of mask-wearing falls largely on the shoulders of government. As COVID-19 continues to spread, governments around the world debated on whether to recommend or mandate the use of masks in public. After the lifting of mandates in several countries, including Canada, responsibility to wear a mask shifted from a collective effort to an individual responsibility. However, Canada’s top doctors still recommend wearing a mask—even without mandates. The conflicting messaging between politicians and public health officials has become more confusing, leaving the decision to wear a mask in public up to individual comfort level. Unfortunately, people need guidance in times of uncertainty and that guidance cannot be nuanced (Capurro et al., 2021). Nuance will only create further confusion and increase potential opportunities for misinformation. As Canadians grow increasingly frustrated with the changing messaging and restrictions one message has become clear. We must now “learn to live with the virus.” But what exactly does living with COVID-19 entail? In order to move forward in a safe manner, there must be better efforts to bridge the gap between politics and science. Public health messaging must consider the motivational roots of health behaviours. In order to encourage individuals to continue to wear face masks without a mandated requirement to do so, strategies to increase collectivist behaviours must be considered. Understanding cultural differences and the power of social norms will provide insight into the current pandemic and help us prepare for future crises. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

|

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed