|

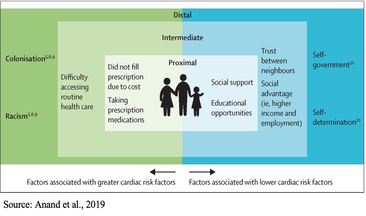

By Katy Cameron, Carleton Graduate Student Author’s Note: I would like to acknowledge that I am but one First Nations voice of many and recognize the diverse and unique experiences of Indigenous People across Turtle Island.  Source: Kamloops This Week, 2021 Source: Kamloops This Week, 2021 We are approaching two years since the initial discovery of the remains of 215 Indigenous children buried at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada. It came as shocking news for some and was a tragic confirmation for many Indigenous Peoples of what had long been suspected. For me, feelings of sadness and despair surfaced for my family and friends who experienced the Residential School system firsthand or were impacted by its legacy effects. Several of these schools were places that separated families, stripped children of their cultural traditions and knowledge, performed experimentations, and turned a blind eye to sexual and violent abuse. Only in the past decade or so has colonialization been acknowledged as a unique social determinant of health for Indigenous Peoples and efforts been made to understand its role in contributing to the disproportionate levels of chronic disease experienced by this population (Reading & Wien, 2009). But how exactly does colonization and its legacy impact the development of chronic disease, and why is this still a problem in 2023?  Source: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, 2022 Source: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, 2022 Diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, and cancer are all examples of chronic diseases in which environmental and/or individual factors promote the development of health conditions that are present for extended periods of time (Earle, 2011). It is commonly known that practicing healthy habits such as eating nutritious foods, getting enough sleep, and regularly exercising contributes to healthier outcomes and reduces the risk of developing chronic diseases and illnesses. Sounds easy enough, right? For many Indigenous people, however, the reality is that there are numerous social barriers to engaging in healthy behaviours. In the first-ever Indigenous Services Canada Annual Report to Parliament in 2020, Indigenous Peoples, especially First Nations living on-reserve, reported lower incomes, less education, reduced employment rates, worse housing conditions, and decreased life expectancy compared to non-Indigenous counterparts. They also reported greater likelihood of being in foster care and higher infant mortality rates, as well as higher rates of violence, victimization, and incarceration. This exemplifies the magnitude of the inequities experienced by this population, and it is understandable why Indigenous Peoples are at greater risk for developing disproportionate rates of disease, illness, and even deaths. Conversely, a study conducted by Anand et al. (2019) found that First Nations communities with higher incomes, better education, increased access to healthcare services, and robust social support mechanisms displayed fewer risk factors for cardiovascular disease compared to communities with overall lower socioeconomic status. Moreover, other research indicates that socioeconomic and lifestyle factors contribute to the high proportion of First Nations who suffer from diabetes (Halseth, 2019). These findings support the position that the social determinants of health play a significant role in contributing to the subsequent development of chronic disease amongst First Nations and other Indigenous groups.  So, how does colonization and its legacy effects tie into chronic health disparities? According to one article, there are proximal, intermediate, and distal social determinants at play. Proximal determinants are those that directly impact healthy behaviours (e.g., physical environment), intermediate determinants are institutional or system-specific (e.g., education level and health care accessibility), and distal determinants are the bigger-picture issues from which many of these factors stem, such as colonialism and racism. Colonialism has been defined as the exploitation, control, and settlement of one country by another (Blakemore, 2019). In Canada, this involved removing autonomy from Indigenous Peoples and using assimilation strategies such as Residential Schools, separating children and families through the Sixties Scoop, and continues today by disproportionately placing Indigenous children in the Child Welfare System (Hobson, 2022). For many Indigenous families, the proximal effects of these initiatives resulted in broken-family dynamics and unstable living situations, depression and overall poor mental health, a loss of sense of self, and substance use. Furthermore, intermediate effects such as a lack of access to, or affordability of, adequate treatment services for these outcomes have ultimately led to intergenerational traumas, and high rates of suicide (Bombay et al., 2014), and we are now seeing higher prevalence rates than ever of chronic diseases like diabetes amongst First Nations youth (Halseth, 2019). If we know that colonialism has shaped both the social determinants and direct health outcomes of Indigenous Peoples (i.e., increased chronic diseases), why do these issues continue to persist?  In 2015, the Canadian Government accepted the final report released by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which outlined 94 Calls to Action targeted at improving Indigenous health, education, and other domains. Although efforts have been made towards addressing these Calls, colonialism persists through current Westernized structural and governance frameworks, policies, and practices that continue to perpetuate the disadvantages and inequalities experienced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada (Blanchet Garneau et al., 2021; Czyzewski, 2011). Prime examples of this can be seen with policing issues, the overrepresentation of Indigenous People in the Canadian criminal justice system (Clarke, 2019), and insufficient culturally sensitive health educational programming, which can result in discrimination and harmful stereotyping (Blanchet Garneau et al., 2021). Increased collaboration and open communication between different levels of government and Indigenous leaders are needed to act on the chronic health disparities we know disproportionately affect Indigenous Peoples. Targeting the social determinants that impact this population, by increasing employment and educational opportunities and guaranteeing equitable access to basic necessities such as adequate healthcare and clean drinking water, is needed in order to ensure better health outcomes for future generations. As we are reminded of the horrific truths about the history of the Residential School system and the effects of colonialization through continued media reports of more unmarked graves, remember that the effects of colonialism are not a thing of the past. In fact, we still see the legacy effects on Indigenous health today, if we are willing to look. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

1 Comment

By Tariro Hlahla, Carleton Neuroscience Student  “Regardless of ethnic background, there is no denying the universal black experience,” writes Health Sciences student Wiza Mkandawire. “This time is paramount to refuel and rejuvenate ourselves, reminding ourselves why exactly it is all worth it.” Similar notions were mirrored in other comments from students - Black History Month is a time to celebrate black people’s achievements. These achievements are nothing short of exceptional, not only historically but in modern times. From the monumental creations in science like the invention of the blood bank by Charles R. Drew to the immense contributions to art and pop culture such as the 2022 Super Bowl Halftime Show being composed primarily of Black music legends like Mary J. Blige and Kendrick Lamar, it’s clear that many Black people have been and continue to be front and centre on the world stage. Yet the Black community continues to face turmoil and oppression. Besides the 2020 George Floyd protests that come to mind, Black people suffer relentless setbacks in almost every aspect of their lives: concrete ceilings and glass cliffs, the harmful stereotype of the diversity hire, the cruel judgement of Black skin colour and hair texture, and so much more. One thing that direly needs to be addressed is supporting Black communities throughout their educational journey, including during their postsecondary education. “[Being a black student] can also feel like being in a very violent struggle, especially when endeavouring to be at the forefront of university leadership and politics,” says Public Affairs and Policy Management student Nikayda Harris. “Having to fight for equal access and representation in residence, in our programs, in the literature and academic works we are exposed to and for our mental health, especially when considering the various traumas that we have faced and have inherited can be tormenting.” According to StatsCan, Black people make up 3.5% of the Canadian population. This means that from a young age, most Black children may not be able to find many Black peers. “I moved from Jamaica to Canada when I was eight years old, and that was already a difficult experience for me in terms of fitting in, as I had a strong accent and I looked and dressed differently,” writes Criminology student Zana Palomino. This sense of alienation can continue far into their academic careers. Just 2 years ago, scandal broke loose when a professor at a prominent Ottawa university used a racial slur that is considered extremely derogatory to Black people and was supported by several of their colleagues. Furthermore, stories have emerged about Canadian Black students being assaulted by police and campus security as a result of racial profiling. Black History Month celebrations within universities mean nothing without acknowledging the cracks in the system. When an entire group of people are not being uplifted by their peers, professors, or protectors, they are being set up for failure. This problem transcends university and spills out into other facets of these students' lives; for example, a Black individual will make on average $12,000 less than their white counterpart. This is an enormous discrepancy in a time when housing is at its least affordable and food prices continue to climb. Despite the copious numbers of setbacks, we have observed something magical begin to form: resilience. According to StatsCan, 44% of Black people believe they have the ability to bounce back from difficult periods in life as opposed to 33% reported in the rest of the population; we also see that almost two thirds of the Black population believe they always learn something from an aversive experience, whereas less than half of the rest of the population endorse this belief. Resilience is a key theme when you ask students about what Black History Month means to them. “[Black History Month to me is] people’s stories and experiences of how they overcame hardships and how they were able to implement change,” comments Biology student Nana Owusu. “Our ancestors have paved the way for us with their sacrifice, strength, courage, and authenticity.” says Health Sciences student Rougayyah Jalloh. Regardless of the struggles that these students must face, they are determined not only to weather the storm, but to come out of the other side stronger than ever. There is certainly much to learn from the Black students who will be among our future doctors, educators, policy makers and more. Resilience is instilled into every Black child from the time they are born to the time they make their way into the world. What non-Black communities must do in order to truly make a difference is to start listening to what Black people have to say. It’s not about creating your own ideas of what Black people need, it’s bringing Black folks into spaces where they can voice their concerns and feel comfortable articulating their unique life experiences. “[Black History Month is] a time to educate oneself on the rich history and is a call to action to continue to advocate for and uplift those within society who are often pushed to the sides,” Psychology student Ashley Igboanugo states. In a world where Black achievements are pushed to the side, stolen by others, downplayed and disregarded, we must take the first step to equity by giving minorities a platform to voice their opinions freely. We need to abolish the stereotypes of the angry ghetto black woman and the aggressive hypermasculine black man and start embracing every facet of Black humanity as it is: colourful, unique, diverse within itself and worthy of consideration. In the month of February, we ought to take time to reflect on the mistakes made and the deep flaws in our society while also rejoicing on the progress we have made. As student Nikayda eloquently states: “If we don’t uplift and honour ourselves and our ancestors, our souls die violent deaths. So until we can reach this promised land of milk, honey and abundant black joy, we take February and we love, we hope, and we remember.”

By Max Kabongo, Carleton Neuroscience Student  As a university student, you will be interacting with people from different cultures or situations. These factors result in a different lived experience than one in which you may be accustomed such as living with a mental illness or constantly being harassed due to racial prejudice. Recently, the case involving the murder of Ahmaud Arbery concluded with the convictions 3 white males for a racially charged hate crime. How do you feel? Thoughts may have gone through your mind such as anger as an innocent man was murdered for being Black. Perhaps you felt relief or happiness knowing that those who are responsible are facing life imprisonment and justice has been served. Without having known Ahmaud Arbery, you may be sharing emotions held by those he was close to; a phenomenon we describe as empathy. Empathy is the ability to share and understand the emotions of others (ex. “I feel what you feel”). It is important to be empathic as to show authenticity when communicating. But what is empathy? How does empathy emerge? Can we enhance it? What is empathy? At the most basic level, empathy is a complex process that seems critical for the formation and maintenance of social bonds. Indeed, understanding how others feel and being able to imagine how others are feeling (independent of our own feelings) may be a hard-wired mechanism to determine when others are in need of support. In short: Empathy helps us to coordinate our emotions and respond to them in others. The ability to do this varies. For instance, we expect greater empathy in those who work in shelters for the homeless, in people choosing to care for a sick relative, or those who are there for a friend after a tough break up. We also know there are individuals that have low levels of empathy, and these individuals appear less able to form social bonds, such as individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). While this does not mean that these individuals do not form social bonds, they do have difficulties interacting socially and understanding that others have feelings different than their own. While many consider empathy a uniquely human trait, there is evidence that non-human animals also show at least some processes associated with empathy. These processes include emotional contagion, theory of mind, and experience/social learning. Emotional contagion (Emotional Empathy). Emotional empathy involves a sensitivity to the emotional state of others, and an awareness of how their emotions affect how we feel. In effect, emotional contagion involves recognizing a particular emotional state in another (i.e., fear, sadness, happiness, anger) and becoming “infected” by their emotional state. This more primitive aspect of empathy can be seen in many species of animals and in humans. For example, rats will show fear when observing a cage mate experience a stressor. Humans also respond to injustices with anger and actions such as ongoing protests in response to police brutality against black people. The capacity to experience emotional empathy in this form appears to be innate. Theory of mind (Cognitive Empathy). Cognitive empathy is the ability to understand that others may be feeling or thinking differently from us, and yet, we are capable of understanding the situation from their perspective. This is referred to as a theory of mind, which is related to perspective taking. For instance, humans are capable of detecting differences between what we think and what others believe our mental state to be. In this sense, the emotions we show to others may not reflect what we feel in order to be mindful of others’ emotions. While non-human animals display emotional empathy, it is more difficult to determine if they demonstrate theory of mind. However, some suggest that highly social animals like elephants, dolphins and chimpanzees are capable of such perspective taking.  Learning and Empathy. There are components of empathy that appear to be strengthened by experience. For instance, one may have emotional reactions to social issues like discrimination, social injustice or lack of access to health care, but the degree of empathy one has for those suffering may be enhanced by personal experience. A person that has been homeless in the past or knows someone close who is homeless, is much more likely to participate in caring for the homeless. Someone who has experienced high levels of pain may display more empathy for a movie character that is going through some traumatic physical experience despite the situation not being real. Thus, empathy can be elicited and enhanced by previous experiences.  So how do all of these aspects of empathy come together? Empathy in the brain Many brain regions are associated with empathy, including the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), a tiny cluster of cells located deep in the middle of the brain. The PVN secretes a hormone called oxytocin, which is thought to be involved in development and maintenance of social bonds and has stress buffering effects. A stressful experience will elicit among other things, the release of oxytocin, and event that may be related to the generation of social support. The effects of oxytocin, together with those of social support during a stressful event may be a critical biological signature of empathy. McQuaid (2015) found increased responsiveness to positive and negative interactions in university students carrying a certain gene polymorphism of the oxytocin receptor which has previously been associated with enhanced empathy. Another region implicated in empathy is the amygdala, a structure nested within the temporal lobe that is crucial for emotional processing, most notably in the context of fear, stress and anxiety. Stressful and traumatic experiences activate the amygdala, leading to a sequence of downstream events which ultimately lead to responses aimed at escaping a threat. Critically, activation of the amygdala leads to a learned association between the stimuli (the sounds, smells, sights) associated with the threat and the experience of the threat, so that these events can be predicted and avoided in the future. Unfortunately, overactivation of the amygdala leads to conditions in which this region becomes stimulated by cues that normally would not produce fear responses, such as anxiety or posttraumatic stress syndrome. This can occur when individuals observe traumatic events happening to others, such as with children in homes where a parent is physically or verbally abused, or when people witness a traumatic event (i.e. a traffic accident, terrorist attack, military combat) in which others are hurt or killed. The amygdala plays an important role in the production of emotional empathy, and in the mechanisms elicited in the face of fearful events. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is a strip of tissue located at the front of the brain containing cells that are connected to several brain regions implicated in memory, emotion, and reward. Interestingly, scientists have discovered that this brain region responds to direct or observed experiences of pain or pleasure. In primates, a subset of cells within the ACC termed “mirror neurons” become activated when observing an experimenter eating a snack that the monkeys had tasted before. Further research on this population of cells suggests these may be implicated in the Theory of Mind: individuals on the Autism Spectrum (who often lack Theory of Mind) have less activation in this brain region when viewing facial images corresponding to different emotional states. Another a brain region called the frontotemporal junction seems to be critical for individuals to imagine themselves in someone else’s shoes. This region develops through childhood. Finally, the prefrontal cortex seems to play a role in human’s ability to understand that the behavior and feelings of others are independent of our own. These three cortical regions form a network that is critical for fully experiencing empathy. Empathy across the life span

How we react to the emotions of others changes throughout development. Evidence of emotional empathy begins to appear during infancy (e.g., when an infant cries while observing another infant crying, or displays facial mimicry). Within the 2-3 of years, a toddler shows more cognitive aspects of empathy such as expressing distress when observing a parent experiencing pain. A toddler’s response to another’s distress may be accompanied by prosocial behaviour such as comforting. These responses are the beginnings of cognitive empathy. Theory of mind begins to develop around the ages of 4-5 as children become aware that others have unique feelings, thoughts, and desires, and that other will respond to their actions when they are happy or displeased. Neurodevelopmental and genetic factors, as well as familial relationships influence how empathy develops across the lifespan. As the brain matures, so does our understanding of the emotions and intentions of others. Unfortunately, in older adult years, those brain regions important for empathy begin to deteriorate. While this does not necessarily produce impairments in understanding the emotions of others, it may produce cognitive alterations that decrease the ability to interpret the motives of others (cognitive perspective-taking), and this has been linked to the increased vulnerability of older adults to being exploited or taken advantage of, for example susceptibility to scamming. Can we enhance empathy? Forming strong social connections allow us to better communicate how we feel. Empathizing with others places a critical role in this process, as it allows us to understand the desires and problems of those around us and to act accordingly. The human brain has been shaped to function in a social context and providing a rich social environment will maintain the cognitive processes that allow for empathy Empathy develops with age and is shaped by our experiences either directly or vicariously. This also entails those emotions and actions of others are addressed as we show support through listening; even to differing opinions or beliefs. It is easier to empathize with those we are close to, such as friends and family. But by informing ourselves of the experiences of others, we can begin to see things from a different perspective. Furthermore, understanding the importance of empathy helps us communicate with others, especially on a university campus.  Katie Vick, Carleton University Student Introduction A common concern expressed by many people throughout the pandemic has been the fear of weight gain from being cooped up inside. Gyms are closed, banana bread recipes are trending, and the weight gain of the coined ‘Quarantine 15’ is on folks’ minds (1,2). Recent research reports negative changes in diet, exercise, and body image worldwide since the pandemic began (3,4,5,6). While one might expect body image comparisons to dissipate with social distancing, this has not been the case. To the contrary, these unprecedented times have forged new opportunities for body image concerns to creep into our consciousness - perhaps in more pervasive ways than before. Social Media Up to 80% of people report spending more time on social media during the pandemic, and this had no doubt been helpful to connect people during isolation,. However, there has been a concurrent shift in the tone of social media content. On the one hand, there is a greater frequency of posts about exercise and diet, and a prevalence of blatantly weight-stigmatizing and fat-phobic body image memes and comparisons, and so it is no surprise that body image issues are rising (7,8). On the other hand, the increased exposure to unrealistic presentations of happiness, accomplishment and appearance can also be harmful. These idealistic posts can prompt social comparisons that are associated with poor self-esteem. I began to notice myself making these comparisons during my morning scroll: Everyone was exercising and eating well… Was I supposed to make my banana bread and eat it too? From what I could tell, everyone on Instagram had their quarantine routine together except for me. Influencers are not only individual sources posting about personal weight-gain concerns. Some nations, such as England, have made it a part of their public health strategy to promote healthy eating and exercise routines throughout lockdown. While well-intentioned, these posts can be harmful to people vulnerable to body image concerns (7,9). When even the government is telling you to do more despite doing everything that you can to just stay sane (which, for some of us, means to avoid compulsively worrying about the number on the scale), it is easy to feel like you aren’t doing enough to be a health goddess.  Video Conferences One study found that video conferencing also affected body satisfaction. Many workplaces have been relying on video conferencing tools during social distancing. We are forced to look at ourselves through others' eyes during video calls much more than we otherwise would. I don’t know about you but having a virtual mirror for three hours of my day is less than ideal, especially when my girlfriends always seem to have their hair and makeup on point in every. single. zoom. call. We usually see our faces directly beside others in the meeting, creating opportunities for direct comparisons (often with many people at once) and self-criticism. Women’s tendency to pay more attention to appearance means that they might be engaging in these comparisons more often, contributing to greater zoom fatigue amongst women compared to men (10). In response, some people have started to use filters to improve their appearance. Using filters can be detrimental by creating unachievable beauty standards, intensifying the problem (11,12). Women have generally reported poorer mental health than men during the pandemic, and this effect exists with body dissatisfaction (13,9). Women reported being more bothered than men by changes in appetite in response to lockdown stress. This might be because women are exposed to more weight-stigmatizing social media messaging. Women also tend to engage in more 'fat talk' or discussions about their pandemic-related weight concerns. I find this particularly interesting with my coworkers, as I have never seen many of their faces due to masking procedures; we have these conversations without even knowing what the other person looks like!  What Now? Experts say that these effects are part of our diet culture (1,2). While the memes might make us feel connected or lift our spirits, they also reinforce the idea of 'good' and 'bad' foods, body shapes and behaviours. The science is clear that weight gain, especially during times of stress (e.g., a global pandemic?!?!) is very complicated. However, social media posts about ‘thinspo,' fad diets, and exercise to avoid lockdown-related weight gain often associate extra pounds with being lazy or unmotivated. This false information can be very stressful. Some people are noticing the return or escalation of unhealthy thoughts and behaviours (9,14,15). Research has found that relationships with food have become more negative throughout the lockdowns, with people restricting and bingeing more than they did pre-pandemic (7,5,6). Some people have reported anxiety about being unable to exercise or to buy guilt-free foods during gym closures and food scarcity (7,6). Due to the unpredictability of lockdowns, for many, what they eat is a form of control (16). With social distancing, there is also little accountability. Friends have confided to me that a ‘lack of supervision’ enabled them to restart unhealthy patterns. Fortunately, some are reaching out, with professionals who were interviewed in Calgary reporting an increased demand for eating disorder supports. In conclusion, the isolation and stress experienced during the COVID-19 lockdowns are hurting our relationships with food and bodies as we spend more time alone and in the digital sphere. We need to continue to pay attention to our loved ones' wellbeing, especially those are predisposed to body image issues, or who have a history of disordered eating. We need to change how we respond to ourselves and others. Instead of validating a friend’s weight concerns, challenge them to be critical of diet culture, identify ways that their bodies feel strong, and acknowledge that their body is doing what it can to keep them healthy and functional in a challenging time. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

|

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed