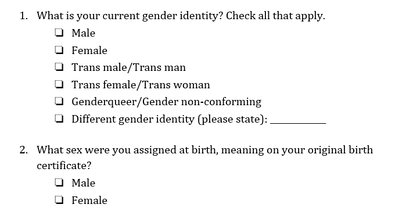

Genderqueer Pride Flag Genderqueer Pride Flag Jaya Rastogi, Health Science, Technology, and Policy MSc Student “For me, going to the doctor is scary and dangerous,” said a genderqueer undergraduate student accessing healthcare in Ontario. “I called my family doctor to ask about [a health service that is unique for genderqueer individuals]. He said ‘I’ve never heard of that. What is that? I don’t know how to do that.’ This says to me that my doctor hasn’t educated himself enough, which seems irresponsible.” The genderqueer and trans community Genderqueer and trans individuals face unique barriers when accessing health care. In 2018, Carleton University’s independent newspaper, the Charlatan, reported on an Algonquin College student, Ashton Schofield, who faced multiple challenges accessing trans-inclusive healthcare in Ottawa. He faced numerous barriers to care including limited providers with enough knowledge to treat trans patients, long wait times for the limited providers, and an incorrect hormone medication prescription (1). Schofield’s story is not unique. As many as 1 in 200 Ontarians are trans and 11% of LGBTQ+ youth are genderqueer/gender nonconforming (2,3). Like Schofield, both genderqueer and trans individuals often face challenges accessing healthcare (4). Genderqueer is a term used to describe an individual who does not conform to one of the two binary genders⁵. Trans is an umbrella term used to describe people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth (5,6). Some genderqueer individuals identify as trans, while others do not (7). Barriers to access and exclusion from healthcare Genderqueer and trans communities face several barriers to accessing trans-inclusive healthcare in Canada, including a lack of relevant and easily available information, self-esteem and mental health issues, challenges finding help, and ongoing experiences of transphobia (8,9). Genderqueer individuals face health-related challenges at even higher rates than binary trans people, including avoiding care due to a fear of discrimination and providers refusing to treat them (10). Genderqueer young people are becoming increasingly visible in healthcare and our communities but are paid little attention when it comes to their unique healthcare needs (9). Trans and genderqueer Canadians also experience social exclusion from healthcare (8). Many medical clinics only have male and female washrooms (11), which communicates to genderqueer individuals that their identity is not welcome in the space. Medical intake forms typically ask patients to select their sex and provide the options of male and female without asking about gender or providing any space for further elaboration (11). This says to genderqueer individuals that their identity is not acknowledged or respected in the health system. Commenting about health intake forms, the genderqueer youth quoted earlier said, “the last medical form I filled out was a form for a blood test and the options were male and female. Since I’m genderqueer I think female and male are just two really small categories.” They continued, “it’s very hard for others to respect me being androgynous. Being genderqueer is the most freeing thing because I’m not confined to these little boxes of sex or gender. Scientists and doctors are supposed to help me, but they’re the ones confining me to these little boxes. They’ll say, ‘you have to pick one or we’re going to pick for you.’ ”  Improving health intake forms Health forms are not set in stone and should be improved to better serve the genderqueer and trans community. Improving health forms is an important step in breaking down barriers to care for genderqueer and trans individuals. A recent Ontario Medical Association (OMA) report (2020) highlighted that a number of factors can lead trans youth to avoid health care (13), including the system’s focus on the gender binary and medical intake forms that ask only if a patient is male or female. A majority of trans youth criticized medical forms for being very male/female centered in a recent Manitoba-based study on trans youth’s experience in the healthcare system (12). Improving health forms would generate accurate data and provide visibility to the genderqueer and trans community. Demonstrating that genderqueer and trans people exist in local hospitals, medical clinics, and communities is important when advocating for inclusive policy, inclusive program creation and funding, and other resource allocation (12,14). The 2-step method for asking sex and gender One tool to improve visibility and accessibility in healthcare is the 2-step method for asking sex and gender, which was developed by the Gender Identity in U.S. Surveillance Group (14). This 2-step method would replace the current 1-step method that only asks a person’s sex and offers male or female as the only response options. In the 2-step method, individuals would be able to differentiate between their sex assigned at birth and their current gender identity while also having multiple options to select for current gender identity. See below for 2-step sex and gender questions (7):  Progress Pride Flag Progress Pride Flag This 2-step method was originally created for surveys but is also recommended for use in health intake forms (15). Recent Canadian research found that the 2-step method captures genderqueer and trans people’s identities better than the 1-step method, validates these identities, and was not confusing to people who are not trans (also called cis) (7). However, the 2-step method was not sufficient for some Indigenous people, and other response options may need to be added to the questions, such as two-spirit (7). There is not enough research to understand if intersex people find that the 2-step method correctly captures their identities (7). Intersex refers to individuals whose hormones or chromosomes create characteristics that are not consistently male or female (7). Additionally, some scholars argue that sex and gender markers should be eliminated wherever they are not necessary (2). While more work needs to be done to ensure questions about sex and gender accurately capture genderqueer and trans peoples’ identities, implementing the 2-step method in health intake forms is a promising step towards making healthcare more accurate and validating for trans and genderqueer individuals.

0 Comments

By Vinussa Rameshshanker, Carleton University Graduate Student  On April 20th, 2021, former police officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty of manslaughter as well as second- and third-degree murder of African American George Floyd last Summer.¹ What began as another instance of institutional racism within the American policing system erupted into an unprecedented, powerful global movement to recognize and transform the systemic discrimination and institutional violence that has disadvantaged people of colour throughout history. Structural racism has been front and center in recent months, referring to the pervasive inequities within the political, economic, and social systems that shape our lives.² Structural racism has repeatedly upheld ‘white privilege’ (both intentionally and unintentionally) at the expense of disadvantaging people of colour in terms of how they live, the opportunities they have access to, and ultimately their wellbeing and quality of life. Race – one of our strongest defining qualities – is a social determinant of health and wellbeing because of the systems we live in. We see racial inequities in all facets of life, whether it be access to safe and secure housing, quality education, or healthcare. We see it now as the COVID-19 pandemic rages on. One year into the pandemic, Canadian communities with the highest concentrations of visible minority populations have had roughly twice the mortality rates of communities with the lowest proportions of racial minorities.³  Without a doubt, yet another aspect of structural racism integral to our wellbeing lies within the systems through which we access food. The time for racial food justice is now. Food justice necessitates questioning the inequities, including those related to race, that structure who produces food, who has access to healthy and nutritious foods, and the kinds of food we eat to nourish us throughout our lives.⁴ We all have the right to adequate food, and the implications of having access to quality nutrition, from childhood to our later years, can be simultaneously obvious and complex. Not only does a healthy and nutritious diet allow us to grow and develop as children, but it also affects how we behave and learn in school, which in turn affects the employment opportunities and standards of living we have as adults. True to the insidious nature of structural racism, the ideal standard of upholding the right to food for all is not immune to racial inequities. For instance, household food insecurity has a strong influence on the academic success of high school students and their transition to higher education,⁵ an undeniable early foundation that paves the way for greater income security and subsequent food security during adulthood.5 However, PROOF (an interdisciplinary Canadian research consortium on food) found that 1 in 8 Canadian households were food insecure in 2017-18.⁶ Even more concerning, the prevalence of food insecurity within Indigenous- and Black-identified households (28.2% and 28.9%, respectively) was almost triple the prevalence of food insecurity amongst White-identified households (11.1%).⁶ A host of factors might explain these disparities, including racialized differences in income, the accessibility of quality and affordable food retailers in the neighbourhood, and housing stability.  Unfortunately, COVID-19 has only exacerbated such inequities. Shortly after the pandemic began, Statistics Canada data highlighted a clear racialized unemployment gap, with visible minority populations facing significantly higher (and in some cases, almost double) rates of unemployment than individuals not of a visible minority or Indigenous identity.⁷ With greater unemployment rates impacting income security for people of colour, the domino effects on household- and community-level food insecurity are not far behind. And so the story of food injustice continues – racial inequities in one system, such as access to economic opportunities, perpetuate inequities in the availability of and access to nutritious foods essential to our health and wellbeing. Once we begin to recognize structural racism within the very systems we inhabit, the natural next step is to identify what can be done, especially given the apparent amplification of inequities tied to the current pandemic. Recognizing the complexity behind structural racism and food security in Canada is a good start, but the purpose of recognition is not complacency. Rather, we must interrogate why such racial inequities exist, whether it be disparities related to job security or the disproportionate levels of racialized communities living in lower income neighbourhoods that lack access to affordable healthy foods.  Even in the mere act of reading these words, there is an inherent privilege and power you hold. Whether you are a student pursuing higher education, or a working professional browsing the web on your downtime, you have a voice and the agency to bring attention to these injustices. As with other sociocultural inequities in health and wellbeing, racialized food injustice and insecurity is an evident problem, but it is also an opportunity. An opportunity to start talking, questioning, and finding ways to act to implement comprehensive solutions that can help push our society towards equitable outcomes in health, wellbeing, and quality of life for all. References:

|

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed