|

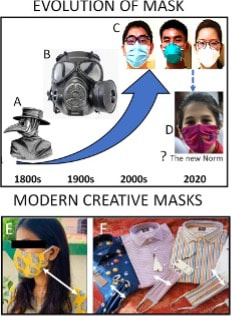

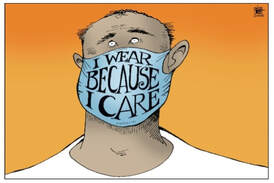

By Emily Tippins, Carleton Graduate Student Face masks have been a predominant symbol of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, mask mandates and mandates in general have been—and continue to be—quite divisive. With conflicting political and scientific messaging about the virus, many individuals are left unsure about the science behind masking and if they should continue to be worn to protect their health and the health of others. Previous studies have speculated that culture plays a fundamental role in shaping people’s response and subsequent health behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Biddlestone et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021). It has become increasingly apparent that behavioural science is essential for understanding and addressing the decisions on whether to refuse or adhere to health guidelines, as well as the influential role that cultural perspectives and political messaging have on these behaviours.  Historically, face masks have played an important role in protecting against the spread of infection (Bakshi et al., 2021). Masks were first aimed to stop bad smells until the 1700s when their medical functions became known. The “miasmatic” theory of disease hypothesized that most diseases were caused by inhaling a “miasma,” thought to be infected air through exposure to corpses and the exhalations of infected individuals (Halliday, 2001). As developments in the field of microbiology were made during the 1800s, miasmatic theory was disproved, and the mask began to transform from the iconic bird-beak masks (see Figure 1; mask A) which were filled with herbal materials thought to keep off the plague, to be more suitable to healthcare needs (see Figure 1; mask C; Lynteris, 2018). As health risks associated with asbestos inhalation became apparent and the risk of the inhalation of toxic dust was identified among mining and construction workers, recommendations were put in place to use masks in workplaces where exposure to harmful chemicals occurs (Goh et al., 2020). Presently, medical technology has advanced, and a large variety of face masks have been developed, many of which are being used by the general population for protection against COVID-19. However, even with the variety of masks available, the data is still unclear on how well they work or when to use them. Earlier this year, a Cochrane review was published suggesting that face masks don’t work in community settings. However, many experts criticized this review’s methodology and assumptions regarding infection transmission and warned that the conclusions are misleading. Contentious political discourse discrediting and discouraging the use of face masks has added to the confusion and decreased public adherence to this protective health behaviour around the world (Bakshi et al., 2021). One identified reason for the lack of compelling evidence on the efficacy of public mask wearing is the lack of controlled trials due to logistical and ethical reasons during the pandemic (Ju et al., 2021). Furthermore, it is thought that the primary route of transmission of COVID-19 is via respiratory particles; however, even this notion has been criticized. A systematic review sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that mask-wearing reduces transmissibility per contact by reducing transmission of infected respiratory particles (Chu et al., 2020). However, the amount of protection you receive from a mask depends on the quality of the mask and how well it fits. Thankfully, guidance from reputable sources like the Public Health Agency of Canada and the WHO have resources on proper COVID-19 mask use. Despite these available resources, many individuals still choose to not wear a mask in public spaces.  We now understand that face masks are most effective when 100% of the individuals in a public space are wearing one (Chu et al., 2020). Therefore, in order for protective face masks (in conjunction with other preventive health measures) to mitigate the transmission of COVID-19, they must be viewed as the standard acceptable behaviour by the general public in order to adopt and maintain this social norm (Bokemper et al., 2021). Research has shown that culture fundamentally shapes how people respond to crises like the COVID-19 pandemic (see Lu et al., 2021). It has also been found that collectivist cultures demonstrate greater adherence to social norms (see Tripathi & Leviatan, 2003). Collectivism encapsulates the tendency to be more concerned with the group’s needs, goals, and interests than with individualistic-oriented interests (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). It has been speculated that a sense of collectivism may improve individuals’ attitudes toward behaviours that involve personal discomfort, such as masking. Places with cultures that are considered to be more collectivist (e.g., Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea) contained the spread of COVID-19 more effectively than places with more individualist cultures (e.g., United States, Spain, and Italy; Biddlestone et al., 2020). Unfortunately, people in individualist cultures often prioritize their personal convenience or preference while ignoring the collective consequences of doing so. For example, although properly fitted masks effectively protect against COVID-19, they can be uncomfortable and create inconvenience. Thus, more community-minded thinking that aligns with collectivist cultural norms would need to be adopted in order to encourage mask-wearing in public settings.  Leadership is critical in adopting collectivist cultural norms (Lu et al., 2021). Unfortunately, the politicization of masks has led some individuals to not fully adopt masking due to political polarization. In fact, some report that choosing to wear a mask may be seen as making a political statement. Policy recommendations and the public acceptability of mask-wearing falls largely on the shoulders of government. As COVID-19 continues to spread, governments around the world debated on whether to recommend or mandate the use of masks in public. After the lifting of mandates in several countries, including Canada, responsibility to wear a mask shifted from a collective effort to an individual responsibility. However, Canada’s top doctors still recommend wearing a mask—even without mandates. The conflicting messaging between politicians and public health officials has become more confusing, leaving the decision to wear a mask in public up to individual comfort level. Unfortunately, people need guidance in times of uncertainty and that guidance cannot be nuanced (Capurro et al., 2021). Nuance will only create further confusion and increase potential opportunities for misinformation. As Canadians grow increasingly frustrated with the changing messaging and restrictions one message has become clear. We must now “learn to live with the virus.” But what exactly does living with COVID-19 entail? In order to move forward in a safe manner, there must be better efforts to bridge the gap between politics and science. Public health messaging must consider the motivational roots of health behaviours. In order to encourage individuals to continue to wear face masks without a mandated requirement to do so, strategies to increase collectivist behaviours must be considered. Understanding cultural differences and the power of social norms will provide insight into the current pandemic and help us prepare for future crises. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

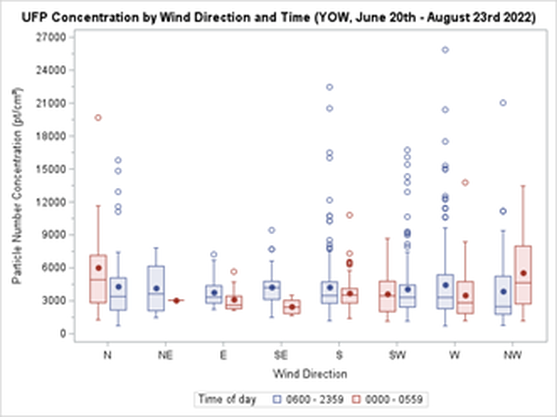

By Kieran Aston Researchers are aware that when it comes to outdoor airborne particulate matter, smaller types of particles are more harmful because they can enter the bloodstream when inhaled. Ultrafine particles (UFPs) are a type of air pollution particulate matter of nanoscale size (less than 100 nm in diameter). To put this into perspective, UFPs are about 1/1000 the diameter of a single strand of human hair. There is growing evidence that long term exposure to UFPs increases the risk of serious health outcomes including cancer, respiratory diseases, hypertension, and diabetes. As we learn more about the dangers of long-term UFP exposure, it becomes increasingly important to learn more about the different sources of UFP emissions and their health impacts. We need to look for ways to reduce exposure. In Canada, the primary source of UFPs is gasoline powered vehicles, but there are many other exposure sources such as diesel emissions and wood burning. That said, one crucial and understudied source of UFPs is aircraft use. Epidemiological studies found that airport related UFP emissions are substantial and may increase the risk of adverse birth outcomes. Since airport-related UFP emissions can spread significantly farther into the surrounding area than roadway-traffic emissions, they pose greater health risks and need to be specifically studied. By design, airport runways run parallel to the prevailing wind direction to create optimal landing and takeoff conditions. Unfortunately, residential areas downwind of airports are subjected to aviation emissions, particularly in cities with little variation in wind direction. During the summer of 2022, I helped collect data for a pilot study of Health Canada’s “Characterization of Aviation-Sourced Air Pollution (CASAP)” project to address UFPs research gaps. The project is led by Keith Van Ryswyk of Health Canada in collaboration with Dr. Paul Villeneuve of the CHAIM Center at Carleton University. The main component of the CASAP study will take place at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport, focusing on investigating the effect of airport-related emissions on the urban areas downwind of the airport. The project will also examine how new, more fuel-efficient landing technology can affect aviation emissions. The pilot study at the Ottawa International Airport was intended to provide an opportunity to fine-tune the methodology for data collection and analysis in preparation for the main study. We set up fixed-site monitoring equipment near a runway at the airport by installing a tripod-like contraption fitted with various instruments that continuously collecting data on pollutants, noise and weather. The site we chose is in line with the runway, and lies to the east of the airport, which is ideal for catching air pollution plumes from aircraft with the prevailing western winds in this area. I was responsible for ensuring that the monitors at the site had everything they needed to collect data on noise, black carbon, and particulate matter at the site. I also contributed to the analysis of the collected data. This meant making weekly visits to the site to replace depleted batteries, clean dirty filters, sync clocks, and offload data, battling mosquitoes and the keep the tech dry during the occasional freakish downpour. I also had to deal with any unexpected errors and mishaps with the devices, of which we had our fair share. A typical Monday for me started with driving out to Albion Road and heading down a more-than-a-little bumpy gravel road to the monitoring site. Once I made my way up a small hill to the monitoring setup, I connected my laptop to each of the devices, downloaded the data, cleared each device’s memory, and synced their clocks. Then, I replaced the devices that were out of battery with fully charged spares and replaced the dirty parts with clean ones. Finally, before leaving I thoroughly checked each instrument to make sure everything was in working order. Since flight data were not yet available at the time of my work on this study, my analysis of the collected data was limited to the effect that wind direction had on UFP concentrations. Some of my preliminary findings showed that UFP concentrations were in general higher during winds that put the monitoring site downwind of the airport (i.e., western winds) than when the monitoring site was upwind of the airport (i.e., during eastern winds), as shown in the graph below. In addition, when comparing UFP concentrations during hours of higher flight traffic (6:00 am – 11:59 pm) and lower flight traffic (12:00 am – 5:59 am), differences seen in both the variability and levels of UFP concentrations were much larger when the monitoring site was downwind of the airport than when it was upwind of the airport. For example, during western winds the standard deviation of recorded particle number concentrations (PNC) was 51.0% larger from 6:00 am – 11:59 pm than it was from 12:00 am – 5:59 am. Conversely, the difference in the standard deviation of PNC during eastern winds was more comparable, being 13.2% larger between 6:00 am – 11:59 pm than it was between 12:00 am – 5:59 am. The project’s next steps include comparing the collected data with flight data to be received from Nav Canada. Flight data allows for a more detailed analysis, and we hope that such an analysis can serve to better inform our methodology for the main portion of the study at Toronto’s Pearson Airport. Our pilot project was the first to collect data on UFPs from aircraft, and in time, we hope to assess whether these exposures impact the health of residents.

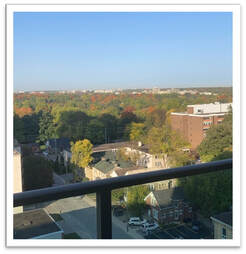

Claire Tizzard, Carleton University Graduate  London, Ontario. October, 2020 London, Ontario. October, 2020 The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we think about a lot of things including the way we travel, how we shop, and even where we live. Early on, as the pandemic containment measures were announced, it seemed that those who could were trading in their urban lives for the peace and tranquility of their rural cottages. Inspired, perhaps, by the wish to escape the higher transmission rates in urban centers but also the increasingly strict restrictions on public space. Those who longed for nature were encouraged to seek rural areas and homes with private backyard space in place of their urban apartments. Given that this is not an accessible option for most people, the role of urban development in the promotion of resilience and well-being has been brought into sharp focus. The thought of urban development might elicit images in our minds of new apartment buildings with large windows and rooftop patios, and while this is not the extent of urban development, it does make up an important part. The architectural features of our living space contribute to our mental health and wellbeing, particularly when we face restrictions on our ability to leave these spaces. The loss of daily routine, social gatherings, and the amalgamation of home and workspace have had a significant impact on mental health and wellbeing, all of which are compounded for those in densely packed urban areas.  A study conducted in Northern Italy, a region that experienced severe lockdown restrictions due to COVID-19, looked at the impact of features of built living spaces on university students found that living in small apartments, lacking a functional balcony, and having a poor view were each associated with moderate to severe depression symptoms (1). These living features are not uncommon as we experience a global trend of movement to urban centers where space is limited. To combat these negative psychological effects, people took to parks and local greenspace. A study that analyzed data from the Google Community Mobility Report found an increase in park visitation from February to May 2020, by over 100%, compared to the same time period the previous year, in Canada, Denmark, and the United Kingdom. Similar increases were found in Spain and Italy once the most strictest lockdown restrictions were lifted (2).  Time outdoors appears to be an important coping strategy. Nature provides an escape from confined living quarters and a time of relaxation to release the stress and anxiety felt most acutely by those in urban centers. Urban greenspaces are not only places to enjoy nature and physical activity but are also places to enjoy social connection. Community gardens and parks help foster social ties that can be maintained safely during social distancing measures to further reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness and foster resilience in a community. A survey of Tokyo residents explored the relationship between mental health scores, outdoor experience, and lifestyle factors to further understand their interaction amidst the increased psychological stress of the coronavirus pandemic. They found that greenspace use and view were both individually associated with higher life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem scores. Greenspace use and view were also both independently associated with lower loneliness, depression and anxiety scores (3). This supports the importance of greenspace in maintaining our mental health and wellbeing through periods of significant stress. However, greenspace is not equally accessible. Data from the Google Community Report found that park visitation and access were correlated with economic, cultural, and social dimensions. Higher socio-economic status communities experienced greater park access and visitation rates, while poverty and unemployment were correlated with reduced park access and visitation (2). Wealthier areas tend to have a greater diversity of species, higher tree cover, and are therefore, less susceptible to environmental changes (4). This inequality in greenspace access could compound the negative effects felt by disadvantaged populations due to COVID-19. Recognizing these data is important in our understanding of the impact of urban development on our wellbeing, especially as we prepare for future pandemics where quarantine measures may again be necessary for preliminary containment. Architectural design should include consideration of living features that have been found to be correlated with positive mental health and wellbeing such as a livable balcony, increased natural lighting, and larger and more functional space, all of which are a function of access to resources and socio-economic status. In addition, urban nature protection and development should be a priority as they have been shown to protect mental wellbeing and foster resilience in communities. Focus should also be brought to increasing equity in the distribution of urban nature development to benefit lower socio-economic communities who are at an increased risk of experiencing negative impacts to wellbeing.  The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we think about a lot of things, including how we appreciate urban greenspaces. They are no longer simply spaces that we enjoy individually, but have become crucial to maintaining our mental health and wellbeing. Urban greenspaces are places for physical activity, stress relief, and community interaction, all of which are key to combatting feelings of loneliness and isolation during lockdown restrictions. As we prepare for future pandemics, urban development that prioritizes greenspace is fundamental to fostering resilience in those who live in urban centers. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

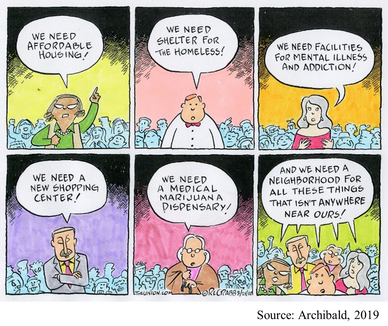

Hilary Ziraldo, Carleton University Student On the day I wrote this, exactly one year had passed since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Like every other day that year, I was at my home in Toronto, only leaving to get groceries or to exercise outside. When I ran into my mom as she headed down the stairs to her basement work-from-home setup, she liked to joke that there was “heavy traffic” on her morning commute. Joking aside, COVID-19 has changed how we interact with our physical environments. We have become increasingly dependent on our homes and neighbourhoods to support our physical and mental health needs, and this has intensified health disparities between those living in adequate and inadequate conditions. The impacts of housing on health are numerous. Overcrowding can increase the spread of communicable infections, while chronic diseases, such as asthma, are associated with substandard heating, insulation and dampness (1,2). Unsafe or unaffordable housing is also a source of chronic stress and can lead to social isolation and poor mental health (2,3,4). Despite these broad consequences, 15.3% of Ontario households live in unsuitable, inadequate or unaffordable conditions, and affordable housing has been consistently de-prioritized by the provincial government (5). I find this alarming because housing is an essential human right, yet continues to be treated as non-essential by government decision-makers and the voting public. Due the high rates of poor-quality and unaffordable housing in Ontario, stay at home orders during the COVID-19 pandemic confined many Ontarians to unhealthy living conditions. Essential workers are also impacted because income is a determinant of housing quality, and the reality is that many frontline jobs are poorly compensated (6). For essential workers living in crowded or intergenerational households, continuing to work puts themselves and their families at greater risk due to both workplace exposures and their household conditions. Beyond housing, our neighbourhoods can have a large impact on health. Residents are more likely to be physically active in safe, walkable neighbourhoods and to choose healthy foods when they are easily accessible (7,8). In neighbourhoods designed to facilitate gatherings, residents perceive greater social support and a stronger sense of community belonging (8). Due to the impact of neighbourhood features on health, vast disparities in health may occur between otherwise geographically close communities. Like quality of housing, quality of neighbourhoods is largely determined by income (6) and this cannot be fixed by simply investing in the development of low-income neighbourhoods. When lower income neighbourhoods are revitalized, gentrification may occur. Gentrification refers to the transformation of the social, economic, cultural, physical and demographic features of a neighbourhood, and often leads to the displacement of long-term and socially marginalized residents (9). In a neighbourhood impacted by gentrification, property and rental values are inflated, pushing vulnerable populations to relocate.  However, there are ways to break the cycle of revitalization and displacement caused by gentrification. The City of Ottawa is incorporating public health concepts into urban growth strategies by creating ‘15-minute neighbourhoods’ (10). A 15-minute neighbourhood is one in which all (or most) daily needs can be accessed within a 15-minute walk from one’s home. The goal of a 15-minute neighbourhood is to reduce reliance on vehicles, increase social connections, and promote equity through improved access to daily needs (10). At the provincial level, Ontario has tried to combat income-based disparities in access to healthy built environments through inclusionary zoning regulations (11). Inclusionary zoning is a strategy to increase affordable housing in desirable neighbourhoods. Under an inclusionary zoning system, every new housing development must be mixed income, meaning that a range of income levels can afford to live in high-quality housing within updated neighbourhoods. Inclusionary zoning has shown some success in the United States, but there is concern that provincial actions will be ineffective at the municipal level. Under the current system, the power to enforce inclusionary zoning lies with municipal governments, that will need to implement bylaws and regulations surrounding the construction of affordable housing units (12). By leaving decisions on inclusionary zoning to municipalities, substantial changes are not guaranteed.  When we understand the magnitude of Ontario’s housing crisis, it is easy to support policy action, like inclusionary zoning. But, take a moment to consider your perspective if affordable housing was proposed in your own neighbourhood? As is too often the case, such a policy might be easy to support until you are personally affected. For residents living near areas allocated for affordable housing, the “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) phenomenon is both common and predictable. The NIMBY phenomenon refers to the opposition of new developments by residents when they believe the development will negatively impact their neighbourhood or property value. Classical examples of the NIMBY phenomenon include responses to safe injection sites and homeless shelters, but affordable housing is similarly affected (13). NIMBY responses are often founded in stereotypes and stigma and serve to perpetuate social inequities. One method governments and developers can use to fight the NIMBY phenomenon is to engage and inform residents throughout the planning process. Importantly, we can individually work against NIMBY-ism by discussing the value of diverse communities with family, friends, and neighbours and being leaders for social equity within our own neighbourhoods. As I sat at my desk in Toronto with the entire province under stay at home orders, I couldn’t help but appreciate how much I relied on my home and neighbourhood over the past year. But, for many Ontarians, hiding away at home has not been a refuge from the dangers of COVID-19. Improving access to healthy homes and neighbourhoods is a complex battle involving political priorities, revitalization and gentrification, and local sentiments. As we move forwards in the COVID-19 pandemic and into its aftermath, we must do more to ensure that “home” is a healthy environment for all Ontarians. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

|

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed