|

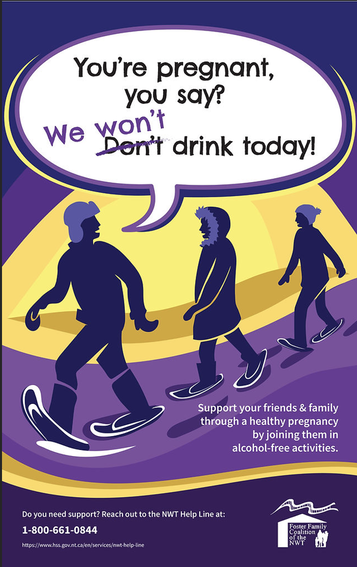

By Jade Alcantara, Carleton Graduate Student I clip my I.D. to a loop on my scrub pants and secure my name tag to my shirt, careful not to cover the acrylic words "NICU." Grabbing a pen, highlighter, and sharpie, I walk over to my patient assignment, where a solid incubator housing a tiny baby welcomes me. Seeing me approach, the nurse flips the patient's binder open for shift report. She skims through the mother's para and gravida that outlines her obstetric history before I interrupt her. "What's her name?" I ask "They haven't given her one yet." "No, the mom's." "Oh, Estella." "And the dad's?" I inquire "Hmm… I'm not sure. You can ask them when they visit tonight." She continues with para and gravida while my eyes skim the page, searching for an oversight. Sure enough, the dad's name is missing. And not just his name, everything. Not a single piece of paternal information is on this baby's kardex. No medical information, health history, anything. For all I know, my patient was miraculously conceived. As I scribble my colleague's updates onto my report sheet, the weight of this realization dawns on me. The document that my colleagues and I record critical updates and base our entire care plan on is missing a page worth of significant information—the father. I spend the rest of the shift bothered by this, cradling my patient, knowing only half her health history.  Fast forward one year later, and I'm still bothered. Perhaps the paternal health history wasn't considered relevant to my scope as a NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) nurse. I'd counter that by saying what concerns my patient concerns me. Rooted in cultural assumptions, women have historically, if not infamously, been deemed the "fetal environment" and treated as such—bearing all the physical, mental, and emotional pressures of fertility, childbearing, and child-rearing (Sharp et al., 2018). This seamless association between women and children set by society may have inadvertently sidelined men despite them being crucial players in family life. Family structures, dynamics, and roles have evolved considerably over the years to improve paternal involvement in family life. But we have yet to see paternal health fully appreciated as a critical contributor to fetal health and development. Just as a woman's health is passed on through her DNA, is the father's health not also passed on to future generations? The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) school of thought would say yes, and goes further still. English physician and epidemiologist David Barker hypothesized that early life nutrition, stress, and other environmental exposures set the stage for obesity, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease in later life (Gluckman et al., 2010). His theory redefined how the world perceived chronic diseases, conceiving a new field of science that would eventually become known as DOHaD. Barker proposed that adverse exposures had three-fold health outcomes—affecting the health of not just one person, one lifespan, but the health of their children and grandchildren (Edwards, 2019; Gluckman et al., 2010; Ryznar et al., 2021).  Recent DOHaD studies have explored the influence of lifestyle behaviours on gamete RNA and the resulting phenotypes observed among offspring (Gluckman et al., 2009; Ryznar et al., 2021). Gamete RNA has been demonstrated to produce offspring with a phenotype associated with their parent's lifestyle and health status (Ryznar et al., 2021). A study that fed mice a Western-like diet observed undesirable metabolic phenotypes among the pups that predisposed them to metabolic diseases and increased the risk of predisposing their future offspring to similar conditions (Grandjean et al., 2016). Likewise, a similar, more favourable observation was made among mice fed a healthy diet (Grandjean et al., 2016). This concept of transgenerational health outcomes, supported by numerous epigenetic studies in rodents, is evidenced in both mothers and fathers (Anway et al., 2006; Daxinger & Whitelaw, 2012; Manikkam et al., 2012; Manikkam et al., 2014; Skinner et al., 2013). Yet much of society, not excluding DOHaD academics, remain fixed on the false assumption that mothers' health is more influential toward fetal health outcomes and precursors of disease vulnerability in later life than fathers' health (Sharp et al., 2018). Operating under this false assumption of maternal "causal primacy" is a dangerous path (Sharp et al., 2018). Not only is it willful ignorance, but it also fuels outdated "cherchez la femme" misconceptions of family health and disease prevention that blame adverse health outcomes on the woman—presenting a misleading bias in research (Sharp et al., 2018). In their article, Sharp et al. (2018) yielded approximately forty paternal-related DOHaD articles compared to seven hundred maternal DOHaD articles. This ratio of research studies between moms and dads illustrates the depth to which these cultural assumptions have taken root and misguided research. The weight put on maternal causal primacy in public health promotion is equally staggering. I can't tell you the number of times I've walked into a public restroom greeted by the same poster. If you're reading this and are a young woman who grew up in Canada, I bet you know precisely which poster I'm talking about. A young lady, smiling and alone, cradling her belly with the words "alcohol and pregnancy don't mix." That poster's been around longer than I could drink. I'm not winding up to throw shade or criticize past health promotion strategies. The poster in question, after all, sparked awareness of fetal alcohol syndrome disorder (FASD) and was surely designed with the best of intentions and is an excellent example of simple but effective messaging. All the same, it's not the messaging nor the purpose I find off-putting but the visual messaging and its contribution to the maternal causal primacy issue. A young lady, smiling and alone. How burdensome. I wonder what the health promotion posters in men's washrooms look like… Why is society so set on making women the poster girls of family life? It's time we adjusted the spotlight and reframed the responsibility. We live in unprecedented times in which social media, technology, and globalization have demonstrated the ability to spread public service announcements and health misinformation like wildfire. We must take up this torch to ensure that the data circulating is credible and that media messaging supports not just men and women, but families. DOHaD studies have found that both men's and women's health influences gene expression and, by extension, healthy development and risk for disease in later life (Sharp et al., 2018). This evidence warrants the redistribution of prenatal health promotion to include both parents. We've all seen the classic "What to expect when you're expecting" book for women, and thankfully, more pregnancy books have expanded their target audience to include dads. We need to see equal representation of mothers and fathers throughout public health promotion strategies. A more recent promotional product for FASD awareness showed a group of people with the caption "Pregnant, you say? We won't drink today! – Support your friends and family through a healthy pregnancy by joining them in alcohol-free activities" (Foster Family Coalition of the Northwest Territories, n.d.). Wordier than the last, sure, but appreciably more meaningful, as supportive messaging goes. As illustrated by the clinical, research, and public health implications, society must champion the responsibility of promoting health for future generations. Family health should be a family effort—shouldered not just by one individual but by a village. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

By Sebastian Steven, Carleton University Graduate  Living in downtown Ottawa means never being far from a demonstration. The nation’s capital is the ideal venue for protests against invasions or displays of solidarity for climate action and social justice. A different kind of demonstration, however, was organized here in early 2022. Stepping outside my apartment near Bank Street dropped me into the “Freedom Convoy.” The Convoy first labelled itself as a protest against a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for truckers crossing the border into the United States but shifted almost immediately into an unlawful occupation of Ottawa streets set on ending all COVID-19 vaccine mandates and removing public health restrictions. The Convoy occupation rallied against undeniably lifesaving measures. There have been significantly fewer deaths due to COVID-19 in individuals who have been vaccinated. Moreover, public health measures (PHMs) for masking, social distancing, and isolation of positive cases have reduced COVID-19 infection. Combined, vaccines and PHMs have spared many from both mild symptoms and severe months-long disabilities that could come from COVID-19 infection. Individuals with ties to and involvement in hate groups organized and participated in this Convoy. However, of interest to this post, some Convoy occupants were more focused on simply opposing PHMs. This subset of participants demonstrated a fundamental misunderstanding of science guiding the pandemic response in Canada during their displays of opposition. Despite aiming to highlight perceived issues with vaccine mandates and PHMs, occupants instead highlighted that some Canadians may not have strong enough knowledge of science and health. Jordan Klepper’s interview with occupants of Rideau St, for example, includes one unvaccinated man who was bewildered that his status means “[he] can’t go to the restaurants, can’t play hockey, and can’t go watch the [Ottawa Senators].” He seemingly views vaccination simply as a method to bar certain individuals of the population from public spaces without acknowledging the science informing these policies. Other knowledge gaps in science and health were seen in Convoy propaganda. Signs questioned scientists' motivations, discounted the value of PHMs, and drew unsupported concerns about deaths from surgeries delayed by COVID-19. These individuals displayed low health literacy during their participation in the Convoy. Health literacy is defined by the World Health Organization as: People’s knowledge, motivation, and competences to access, understand, and appraise health information in order to make judgments and take decisions in every-day life concerning health care, disease prevention, and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course. Equipping Canadians with skills in health literacy can enhance one’s ability to understand their health status and improve it. Health literacy is displayed, for example, when one can collect and understand information surrounding the risk of COVID-19 to then take steps to mitigate infection. The ability to do this, though, varies among Canadians. Estimates from 2008 show that 60% of Canadian adults are unable to obtain, understand, and act upon health information shared with them. This alarming statistic is more problematic with no national update to this estimate since 2008. Granted, the number of participants in the Convoy was minimal compared to the entire population of Canada. However, the occupation made it obvious that there are still Canadians who have not achieved sufficient health literacy. Convoy propaganda showed that low health literacy continues to be a significant problem in Canada into 2022. Some occupants who rallied against PHMs, for example, may not have the knowledge to take in the evidence showing that these measures increase safety for an entire population. The unvaccinated man interviewed by Klepper may not have been exposed to accessible health messaging describing that entering high-risk environments without being vaccinated puts himself in much higher danger of being infected with and dying from COVID-19. Shifting from a mindset that lacks concrete health and science-related knowledge to a more informed viewpoint would demonstrate improved health literacy. Health literacy, though, is not an issue of solely individual level factors. It is a social determinant of health (SDoH). This term refers to the unique living conditions one experiences that shape their health. SDoH are often influenced by systemic issues (e.g., socio-economic status, education level, etc.) that cause general societal inequities. Health literacy falls in line with this. Lower-income Canadians, for example, tend to have lower health literacy skills. A similar trend has been seen in Canadians with no post-secondary education. Individuals with little educational background are more likely to have insufficient health literacy skills. Children, even, receive most of their knowledge related to COVID-19 from parents, suggesting that one’s health literacy may be influenced by and sustained through generations. In total, research has demonstrated how engrained health literacy is as a SDoH. Importantly, gaps in health literacy have direct effects on the health of an individual and the population. Individuals who have both chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder and low health literacy skills, for example, tend to have a lower quality of life. Other general findings show that individuals with combined chronic illness and low health literacy skills have higher rates of mortality from their illness. These findings are especially troubling knowing that the proportion of older adults in the Canadian population will increase in the coming years. Improving national health literacy could therefore reduce the burden on the Canadian health care system for the care of chronic illnesses that will become increasingly prevalent in an aging population. Improving health literacy across a population could also empower individuals in subsequent pandemics to understand public health messaging and incorporate it into health behaviours that keep all members of society safe. Many existing definitions of health literacy do not adequately acknowledge the very real influence of the SDoH. As a result, interventions to improve health literacy may be too narrowly focused on individual factors. The Convoy shows, instead, that population-level interventions guided by the SDoH make more sense. The occupants did not exist solely within themselves but were members of diverse families, earners of varying incomes, and with varied educational backgrounds. These factors are large-scale SDoH that influence health literacy levels and overall health. This may be why previous attempts at improving health literacy in a one-on-one clinical setting have largely failed to make great impacts on health outcomes; issues influenced by large systemic factors cannot be fixed by small-scale individual level interventions. Community-based interventions have been suggested as a possible method by which to bolster skills in health literacy. Attempting to improve the health literacy skills of entire communities aligns with the knowledge that health literacy is a SDoH and addresses previously stated concerns. Research suggests that programs should be tailored to the unique SDoH of each community. This would require developing intervention tools that are specific to the community’s culture. This could include pairing health literacy skill workshops, for example, with programs that aim to improve other influential SDoH like education and income. Population-level interventions like these could have a much broader effect on the health of Canadians because they would inherently account for the large systemic influences that dictate skills in health literacy. Downtown Ottawa continues to be a stage to discuss current issues in Canadian society. Though the Freedom Convoy occupants may have felt they were putting on a performance solely to rally against pandemic-related issues, they were, in fact, bringing a different fundamental Canadian issue to the spotlight. The Convoy showed that we must improve the health literacy of Canadians. Doing so is imperative because health literacy is a SDoH with definite influence over the general health of individual Canadians. Health literacy must be addressed if we wish to improve the health of Canadians. Taking action on this issue could even prevent future disruptive occupations during public health crises. The exasperated residents of Ottawa and those occupying the city streets could both be helped by viewing such issues through the lens of health literacy. Though, I admit, this is a difficult mindset change to make, speaking as one of those exasperated Ottawa citizens living in the middle of the occupation. That being said, my background in health sciences has taught me that addressing issues at the systemic level is often the best way to bring about meaningful change. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course

Katie Vick, Carleton University Student Introduction A common concern expressed by many people throughout the pandemic has been the fear of weight gain from being cooped up inside. Gyms are closed, banana bread recipes are trending, and the weight gain of the coined ‘Quarantine 15’ is on folks’ minds (1,2). Recent research reports negative changes in diet, exercise, and body image worldwide since the pandemic began (3,4,5,6). While one might expect body image comparisons to dissipate with social distancing, this has not been the case. To the contrary, these unprecedented times have forged new opportunities for body image concerns to creep into our consciousness - perhaps in more pervasive ways than before. Social Media Up to 80% of people report spending more time on social media during the pandemic, and this had no doubt been helpful to connect people during isolation,. However, there has been a concurrent shift in the tone of social media content. On the one hand, there is a greater frequency of posts about exercise and diet, and a prevalence of blatantly weight-stigmatizing and fat-phobic body image memes and comparisons, and so it is no surprise that body image issues are rising (7,8). On the other hand, the increased exposure to unrealistic presentations of happiness, accomplishment and appearance can also be harmful. These idealistic posts can prompt social comparisons that are associated with poor self-esteem. I began to notice myself making these comparisons during my morning scroll: Everyone was exercising and eating well… Was I supposed to make my banana bread and eat it too? From what I could tell, everyone on Instagram had their quarantine routine together except for me. Influencers are not only individual sources posting about personal weight-gain concerns. Some nations, such as England, have made it a part of their public health strategy to promote healthy eating and exercise routines throughout lockdown. While well-intentioned, these posts can be harmful to people vulnerable to body image concerns (7,9). When even the government is telling you to do more despite doing everything that you can to just stay sane (which, for some of us, means to avoid compulsively worrying about the number on the scale), it is easy to feel like you aren’t doing enough to be a health goddess.  Video Conferences One study found that video conferencing also affected body satisfaction. Many workplaces have been relying on video conferencing tools during social distancing. We are forced to look at ourselves through others' eyes during video calls much more than we otherwise would. I don’t know about you but having a virtual mirror for three hours of my day is less than ideal, especially when my girlfriends always seem to have their hair and makeup on point in every. single. zoom. call. We usually see our faces directly beside others in the meeting, creating opportunities for direct comparisons (often with many people at once) and self-criticism. Women’s tendency to pay more attention to appearance means that they might be engaging in these comparisons more often, contributing to greater zoom fatigue amongst women compared to men (10). In response, some people have started to use filters to improve their appearance. Using filters can be detrimental by creating unachievable beauty standards, intensifying the problem (11,12). Women have generally reported poorer mental health than men during the pandemic, and this effect exists with body dissatisfaction (13,9). Women reported being more bothered than men by changes in appetite in response to lockdown stress. This might be because women are exposed to more weight-stigmatizing social media messaging. Women also tend to engage in more 'fat talk' or discussions about their pandemic-related weight concerns. I find this particularly interesting with my coworkers, as I have never seen many of their faces due to masking procedures; we have these conversations without even knowing what the other person looks like!  What Now? Experts say that these effects are part of our diet culture (1,2). While the memes might make us feel connected or lift our spirits, they also reinforce the idea of 'good' and 'bad' foods, body shapes and behaviours. The science is clear that weight gain, especially during times of stress (e.g., a global pandemic?!?!) is very complicated. However, social media posts about ‘thinspo,' fad diets, and exercise to avoid lockdown-related weight gain often associate extra pounds with being lazy or unmotivated. This false information can be very stressful. Some people are noticing the return or escalation of unhealthy thoughts and behaviours (9,14,15). Research has found that relationships with food have become more negative throughout the lockdowns, with people restricting and bingeing more than they did pre-pandemic (7,5,6). Some people have reported anxiety about being unable to exercise or to buy guilt-free foods during gym closures and food scarcity (7,6). Due to the unpredictability of lockdowns, for many, what they eat is a form of control (16). With social distancing, there is also little accountability. Friends have confided to me that a ‘lack of supervision’ enabled them to restart unhealthy patterns. Fortunately, some are reaching out, with professionals who were interviewed in Calgary reporting an increased demand for eating disorder supports. In conclusion, the isolation and stress experienced during the COVID-19 lockdowns are hurting our relationships with food and bodies as we spend more time alone and in the digital sphere. We need to continue to pay attention to our loved ones' wellbeing, especially those are predisposed to body image issues, or who have a history of disordered eating. We need to change how we respond to ourselves and others. Instead of validating a friend’s weight concerns, challenge them to be critical of diet culture, identify ways that their bodies feel strong, and acknowledge that their body is doing what it can to keep them healthy and functional in a challenging time. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

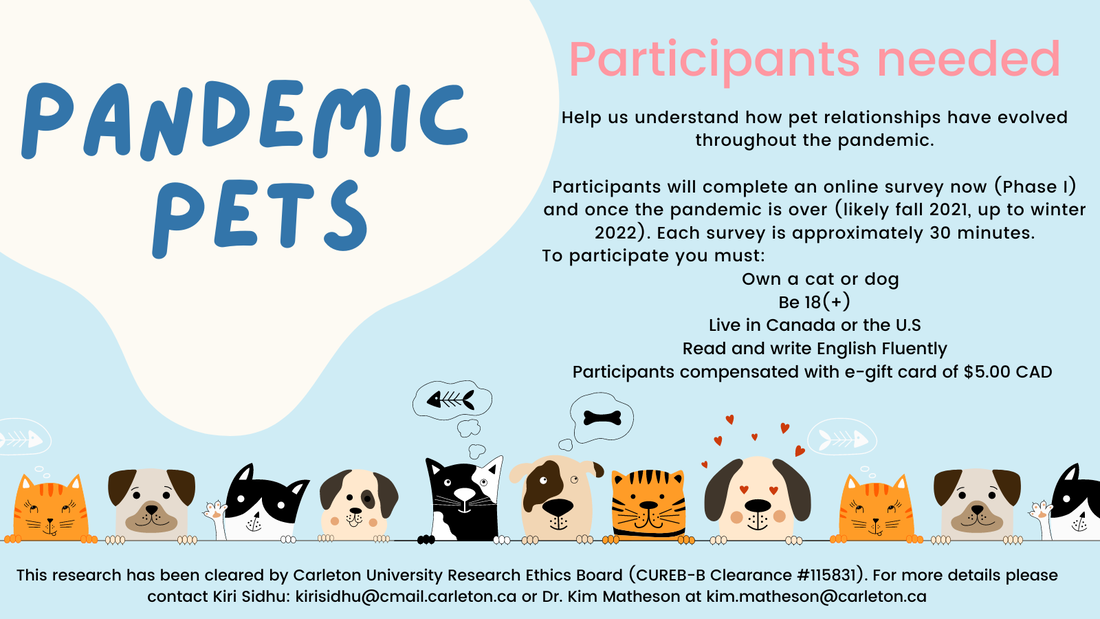

Pandemic Pets aims to understand how our relationships with our pets have evolved over the course of the pandemic, and how they might change after the pandemic. Currently, we are looking for participants to help us to understand this process.

You will be asked to complete an online survey now, and after the pandemic (likely fall of 2021 or winter of 2022, pending health restrictions). For your time you will be compensated by either an Amazon, or other ethical shopping site e-gift card of $5.00 CAN, or a donation of equal value to an animal shelter, for completing each survey. Your participation at each time point is entirely voluntary, and you may withdraw at any time. Each survey takes approximately 25-30 minutes, and your responses will be confidential. To be eligible, you must be 18 or older, own a cat or dog, living in Canada or the U.S., and fluent in English. There are no physical risks in this study but you may experience mild discomfort when responding to questions on stress, feelings of loneliness, or mood. If you are interested, please go to: https://carletonu.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_7WID0smvpkCxHw2 or email Sarah Kirkpatrick-Wahl at [email protected] or Kiri Sidhu at [email protected]. You may also contact Dr. Kim Matheson at [email protected] The ethics for this project have been approved by the Research Ethics Board at Carleton University (Clearance #115831). If you have any ethical concerns about this study, please contact the Carleton University Research Ethics Board-B by email at [email protected]. |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed