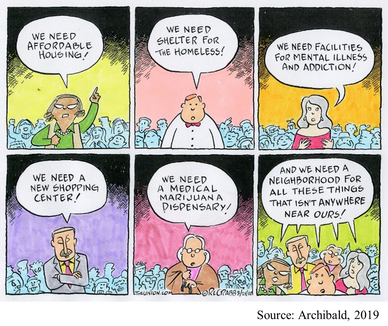

Hilary Ziraldo, Carleton University Student On the day I wrote this, exactly one year had passed since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Like every other day that year, I was at my home in Toronto, only leaving to get groceries or to exercise outside. When I ran into my mom as she headed down the stairs to her basement work-from-home setup, she liked to joke that there was “heavy traffic” on her morning commute. Joking aside, COVID-19 has changed how we interact with our physical environments. We have become increasingly dependent on our homes and neighbourhoods to support our physical and mental health needs, and this has intensified health disparities between those living in adequate and inadequate conditions. The impacts of housing on health are numerous. Overcrowding can increase the spread of communicable infections, while chronic diseases, such as asthma, are associated with substandard heating, insulation and dampness (1,2). Unsafe or unaffordable housing is also a source of chronic stress and can lead to social isolation and poor mental health (2,3,4). Despite these broad consequences, 15.3% of Ontario households live in unsuitable, inadequate or unaffordable conditions, and affordable housing has been consistently de-prioritized by the provincial government (5). I find this alarming because housing is an essential human right, yet continues to be treated as non-essential by government decision-makers and the voting public. Due the high rates of poor-quality and unaffordable housing in Ontario, stay at home orders during the COVID-19 pandemic confined many Ontarians to unhealthy living conditions. Essential workers are also impacted because income is a determinant of housing quality, and the reality is that many frontline jobs are poorly compensated (6). For essential workers living in crowded or intergenerational households, continuing to work puts themselves and their families at greater risk due to both workplace exposures and their household conditions. Beyond housing, our neighbourhoods can have a large impact on health. Residents are more likely to be physically active in safe, walkable neighbourhoods and to choose healthy foods when they are easily accessible (7,8). In neighbourhoods designed to facilitate gatherings, residents perceive greater social support and a stronger sense of community belonging (8). Due to the impact of neighbourhood features on health, vast disparities in health may occur between otherwise geographically close communities. Like quality of housing, quality of neighbourhoods is largely determined by income (6) and this cannot be fixed by simply investing in the development of low-income neighbourhoods. When lower income neighbourhoods are revitalized, gentrification may occur. Gentrification refers to the transformation of the social, economic, cultural, physical and demographic features of a neighbourhood, and often leads to the displacement of long-term and socially marginalized residents (9). In a neighbourhood impacted by gentrification, property and rental values are inflated, pushing vulnerable populations to relocate.  However, there are ways to break the cycle of revitalization and displacement caused by gentrification. The City of Ottawa is incorporating public health concepts into urban growth strategies by creating ‘15-minute neighbourhoods’ (10). A 15-minute neighbourhood is one in which all (or most) daily needs can be accessed within a 15-minute walk from one’s home. The goal of a 15-minute neighbourhood is to reduce reliance on vehicles, increase social connections, and promote equity through improved access to daily needs (10). At the provincial level, Ontario has tried to combat income-based disparities in access to healthy built environments through inclusionary zoning regulations (11). Inclusionary zoning is a strategy to increase affordable housing in desirable neighbourhoods. Under an inclusionary zoning system, every new housing development must be mixed income, meaning that a range of income levels can afford to live in high-quality housing within updated neighbourhoods. Inclusionary zoning has shown some success in the United States, but there is concern that provincial actions will be ineffective at the municipal level. Under the current system, the power to enforce inclusionary zoning lies with municipal governments, that will need to implement bylaws and regulations surrounding the construction of affordable housing units (12). By leaving decisions on inclusionary zoning to municipalities, substantial changes are not guaranteed.  When we understand the magnitude of Ontario’s housing crisis, it is easy to support policy action, like inclusionary zoning. But, take a moment to consider your perspective if affordable housing was proposed in your own neighbourhood? As is too often the case, such a policy might be easy to support until you are personally affected. For residents living near areas allocated for affordable housing, the “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) phenomenon is both common and predictable. The NIMBY phenomenon refers to the opposition of new developments by residents when they believe the development will negatively impact their neighbourhood or property value. Classical examples of the NIMBY phenomenon include responses to safe injection sites and homeless shelters, but affordable housing is similarly affected (13). NIMBY responses are often founded in stereotypes and stigma and serve to perpetuate social inequities. One method governments and developers can use to fight the NIMBY phenomenon is to engage and inform residents throughout the planning process. Importantly, we can individually work against NIMBY-ism by discussing the value of diverse communities with family, friends, and neighbours and being leaders for social equity within our own neighbourhoods. As I sat at my desk in Toronto with the entire province under stay at home orders, I couldn’t help but appreciate how much I relied on my home and neighbourhood over the past year. But, for many Ontarians, hiding away at home has not been a refuge from the dangers of COVID-19. Improving access to healthy homes and neighbourhoods is a complex battle involving political priorities, revitalization and gentrification, and local sentiments. As we move forwards in the COVID-19 pandemic and into its aftermath, we must do more to ensure that “home” is a healthy environment for all Ontarians. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

Katie Vick, Carleton University Student Introduction A common concern expressed by many people throughout the pandemic has been the fear of weight gain from being cooped up inside. Gyms are closed, banana bread recipes are trending, and the weight gain of the coined ‘Quarantine 15’ is on folks’ minds (1,2). Recent research reports negative changes in diet, exercise, and body image worldwide since the pandemic began (3,4,5,6). While one might expect body image comparisons to dissipate with social distancing, this has not been the case. To the contrary, these unprecedented times have forged new opportunities for body image concerns to creep into our consciousness - perhaps in more pervasive ways than before. Social Media Up to 80% of people report spending more time on social media during the pandemic, and this had no doubt been helpful to connect people during isolation,. However, there has been a concurrent shift in the tone of social media content. On the one hand, there is a greater frequency of posts about exercise and diet, and a prevalence of blatantly weight-stigmatizing and fat-phobic body image memes and comparisons, and so it is no surprise that body image issues are rising (7,8). On the other hand, the increased exposure to unrealistic presentations of happiness, accomplishment and appearance can also be harmful. These idealistic posts can prompt social comparisons that are associated with poor self-esteem. I began to notice myself making these comparisons during my morning scroll: Everyone was exercising and eating well… Was I supposed to make my banana bread and eat it too? From what I could tell, everyone on Instagram had their quarantine routine together except for me. Influencers are not only individual sources posting about personal weight-gain concerns. Some nations, such as England, have made it a part of their public health strategy to promote healthy eating and exercise routines throughout lockdown. While well-intentioned, these posts can be harmful to people vulnerable to body image concerns (7,9). When even the government is telling you to do more despite doing everything that you can to just stay sane (which, for some of us, means to avoid compulsively worrying about the number on the scale), it is easy to feel like you aren’t doing enough to be a health goddess.  Video Conferences One study found that video conferencing also affected body satisfaction. Many workplaces have been relying on video conferencing tools during social distancing. We are forced to look at ourselves through others' eyes during video calls much more than we otherwise would. I don’t know about you but having a virtual mirror for three hours of my day is less than ideal, especially when my girlfriends always seem to have their hair and makeup on point in every. single. zoom. call. We usually see our faces directly beside others in the meeting, creating opportunities for direct comparisons (often with many people at once) and self-criticism. Women’s tendency to pay more attention to appearance means that they might be engaging in these comparisons more often, contributing to greater zoom fatigue amongst women compared to men (10). In response, some people have started to use filters to improve their appearance. Using filters can be detrimental by creating unachievable beauty standards, intensifying the problem (11,12). Women have generally reported poorer mental health than men during the pandemic, and this effect exists with body dissatisfaction (13,9). Women reported being more bothered than men by changes in appetite in response to lockdown stress. This might be because women are exposed to more weight-stigmatizing social media messaging. Women also tend to engage in more 'fat talk' or discussions about their pandemic-related weight concerns. I find this particularly interesting with my coworkers, as I have never seen many of their faces due to masking procedures; we have these conversations without even knowing what the other person looks like!  What Now? Experts say that these effects are part of our diet culture (1,2). While the memes might make us feel connected or lift our spirits, they also reinforce the idea of 'good' and 'bad' foods, body shapes and behaviours. The science is clear that weight gain, especially during times of stress (e.g., a global pandemic?!?!) is very complicated. However, social media posts about ‘thinspo,' fad diets, and exercise to avoid lockdown-related weight gain often associate extra pounds with being lazy or unmotivated. This false information can be very stressful. Some people are noticing the return or escalation of unhealthy thoughts and behaviours (9,14,15). Research has found that relationships with food have become more negative throughout the lockdowns, with people restricting and bingeing more than they did pre-pandemic (7,5,6). Some people have reported anxiety about being unable to exercise or to buy guilt-free foods during gym closures and food scarcity (7,6). Due to the unpredictability of lockdowns, for many, what they eat is a form of control (16). With social distancing, there is also little accountability. Friends have confided to me that a ‘lack of supervision’ enabled them to restart unhealthy patterns. Fortunately, some are reaching out, with professionals who were interviewed in Calgary reporting an increased demand for eating disorder supports. In conclusion, the isolation and stress experienced during the COVID-19 lockdowns are hurting our relationships with food and bodies as we spend more time alone and in the digital sphere. We need to continue to pay attention to our loved ones' wellbeing, especially those are predisposed to body image issues, or who have a history of disordered eating. We need to change how we respond to ourselves and others. Instead of validating a friend’s weight concerns, challenge them to be critical of diet culture, identify ways that their bodies feel strong, and acknowledge that their body is doing what it can to keep them healthy and functional in a challenging time. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

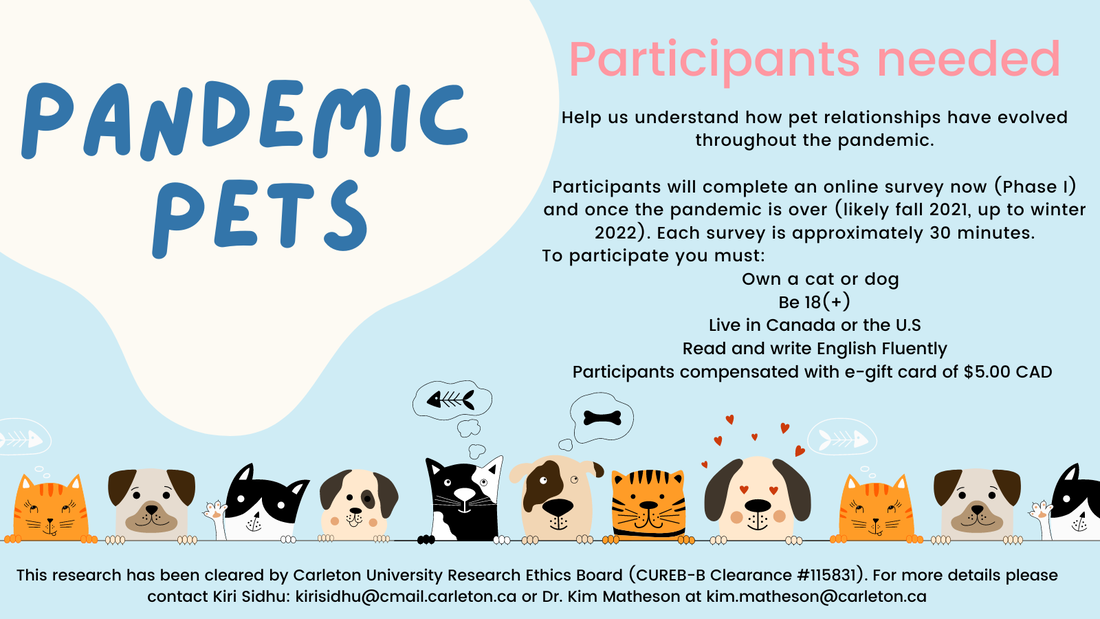

Pandemic Pets aims to understand how our relationships with our pets have evolved over the course of the pandemic, and how they might change after the pandemic. Currently, we are looking for participants to help us to understand this process.

You will be asked to complete an online survey now, and after the pandemic (likely fall of 2021 or winter of 2022, pending health restrictions). For your time you will be compensated by either an Amazon, or other ethical shopping site e-gift card of $5.00 CAN, or a donation of equal value to an animal shelter, for completing each survey. Your participation at each time point is entirely voluntary, and you may withdraw at any time. Each survey takes approximately 25-30 minutes, and your responses will be confidential. To be eligible, you must be 18 or older, own a cat or dog, living in Canada or the U.S., and fluent in English. There are no physical risks in this study but you may experience mild discomfort when responding to questions on stress, feelings of loneliness, or mood. If you are interested, please go to: https://carletonu.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_7WID0smvpkCxHw2 or email Sarah Kirkpatrick-Wahl at [email protected] or Kiri Sidhu at [email protected]. You may also contact Dr. Kim Matheson at [email protected] The ethics for this project have been approved by the Research Ethics Board at Carleton University (Clearance #115831). If you have any ethical concerns about this study, please contact the Carleton University Research Ethics Board-B by email at [email protected]. |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed