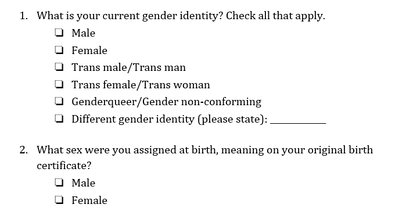

Genderqueer Pride Flag Genderqueer Pride Flag Jaya Rastogi, Health Science, Technology, and Policy MSc Student “For me, going to the doctor is scary and dangerous,” said a genderqueer undergraduate student accessing healthcare in Ontario. “I called my family doctor to ask about [a health service that is unique for genderqueer individuals]. He said ‘I’ve never heard of that. What is that? I don’t know how to do that.’ This says to me that my doctor hasn’t educated himself enough, which seems irresponsible.” The genderqueer and trans community Genderqueer and trans individuals face unique barriers when accessing health care. In 2018, Carleton University’s independent newspaper, the Charlatan, reported on an Algonquin College student, Ashton Schofield, who faced multiple challenges accessing trans-inclusive healthcare in Ottawa. He faced numerous barriers to care including limited providers with enough knowledge to treat trans patients, long wait times for the limited providers, and an incorrect hormone medication prescription (1). Schofield’s story is not unique. As many as 1 in 200 Ontarians are trans and 11% of LGBTQ+ youth are genderqueer/gender nonconforming (2,3). Like Schofield, both genderqueer and trans individuals often face challenges accessing healthcare (4). Genderqueer is a term used to describe an individual who does not conform to one of the two binary genders⁵. Trans is an umbrella term used to describe people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth (5,6). Some genderqueer individuals identify as trans, while others do not (7). Barriers to access and exclusion from healthcare Genderqueer and trans communities face several barriers to accessing trans-inclusive healthcare in Canada, including a lack of relevant and easily available information, self-esteem and mental health issues, challenges finding help, and ongoing experiences of transphobia (8,9). Genderqueer individuals face health-related challenges at even higher rates than binary trans people, including avoiding care due to a fear of discrimination and providers refusing to treat them (10). Genderqueer young people are becoming increasingly visible in healthcare and our communities but are paid little attention when it comes to their unique healthcare needs (9). Trans and genderqueer Canadians also experience social exclusion from healthcare (8). Many medical clinics only have male and female washrooms (11), which communicates to genderqueer individuals that their identity is not welcome in the space. Medical intake forms typically ask patients to select their sex and provide the options of male and female without asking about gender or providing any space for further elaboration (11). This says to genderqueer individuals that their identity is not acknowledged or respected in the health system. Commenting about health intake forms, the genderqueer youth quoted earlier said, “the last medical form I filled out was a form for a blood test and the options were male and female. Since I’m genderqueer I think female and male are just two really small categories.” They continued, “it’s very hard for others to respect me being androgynous. Being genderqueer is the most freeing thing because I’m not confined to these little boxes of sex or gender. Scientists and doctors are supposed to help me, but they’re the ones confining me to these little boxes. They’ll say, ‘you have to pick one or we’re going to pick for you.’ ”  Improving health intake forms Health forms are not set in stone and should be improved to better serve the genderqueer and trans community. Improving health forms is an important step in breaking down barriers to care for genderqueer and trans individuals. A recent Ontario Medical Association (OMA) report (2020) highlighted that a number of factors can lead trans youth to avoid health care (13), including the system’s focus on the gender binary and medical intake forms that ask only if a patient is male or female. A majority of trans youth criticized medical forms for being very male/female centered in a recent Manitoba-based study on trans youth’s experience in the healthcare system (12). Improving health forms would generate accurate data and provide visibility to the genderqueer and trans community. Demonstrating that genderqueer and trans people exist in local hospitals, medical clinics, and communities is important when advocating for inclusive policy, inclusive program creation and funding, and other resource allocation (12,14). The 2-step method for asking sex and gender One tool to improve visibility and accessibility in healthcare is the 2-step method for asking sex and gender, which was developed by the Gender Identity in U.S. Surveillance Group (14). This 2-step method would replace the current 1-step method that only asks a person’s sex and offers male or female as the only response options. In the 2-step method, individuals would be able to differentiate between their sex assigned at birth and their current gender identity while also having multiple options to select for current gender identity. See below for 2-step sex and gender questions (7):  Progress Pride Flag Progress Pride Flag This 2-step method was originally created for surveys but is also recommended for use in health intake forms (15). Recent Canadian research found that the 2-step method captures genderqueer and trans people’s identities better than the 1-step method, validates these identities, and was not confusing to people who are not trans (also called cis) (7). However, the 2-step method was not sufficient for some Indigenous people, and other response options may need to be added to the questions, such as two-spirit (7). There is not enough research to understand if intersex people find that the 2-step method correctly captures their identities (7). Intersex refers to individuals whose hormones or chromosomes create characteristics that are not consistently male or female (7). Additionally, some scholars argue that sex and gender markers should be eliminated wherever they are not necessary (2). While more work needs to be done to ensure questions about sex and gender accurately capture genderqueer and trans peoples’ identities, implementing the 2-step method in health intake forms is a promising step towards making healthcare more accurate and validating for trans and genderqueer individuals.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed