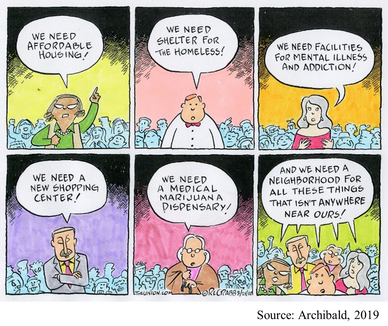

Hilary Ziraldo, Carleton University Student On the day I wrote this, exactly one year had passed since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Like every other day that year, I was at my home in Toronto, only leaving to get groceries or to exercise outside. When I ran into my mom as she headed down the stairs to her basement work-from-home setup, she liked to joke that there was “heavy traffic” on her morning commute. Joking aside, COVID-19 has changed how we interact with our physical environments. We have become increasingly dependent on our homes and neighbourhoods to support our physical and mental health needs, and this has intensified health disparities between those living in adequate and inadequate conditions. The impacts of housing on health are numerous. Overcrowding can increase the spread of communicable infections, while chronic diseases, such as asthma, are associated with substandard heating, insulation and dampness (1,2). Unsafe or unaffordable housing is also a source of chronic stress and can lead to social isolation and poor mental health (2,3,4). Despite these broad consequences, 15.3% of Ontario households live in unsuitable, inadequate or unaffordable conditions, and affordable housing has been consistently de-prioritized by the provincial government (5). I find this alarming because housing is an essential human right, yet continues to be treated as non-essential by government decision-makers and the voting public. Due the high rates of poor-quality and unaffordable housing in Ontario, stay at home orders during the COVID-19 pandemic confined many Ontarians to unhealthy living conditions. Essential workers are also impacted because income is a determinant of housing quality, and the reality is that many frontline jobs are poorly compensated (6). For essential workers living in crowded or intergenerational households, continuing to work puts themselves and their families at greater risk due to both workplace exposures and their household conditions. Beyond housing, our neighbourhoods can have a large impact on health. Residents are more likely to be physically active in safe, walkable neighbourhoods and to choose healthy foods when they are easily accessible (7,8). In neighbourhoods designed to facilitate gatherings, residents perceive greater social support and a stronger sense of community belonging (8). Due to the impact of neighbourhood features on health, vast disparities in health may occur between otherwise geographically close communities. Like quality of housing, quality of neighbourhoods is largely determined by income (6) and this cannot be fixed by simply investing in the development of low-income neighbourhoods. When lower income neighbourhoods are revitalized, gentrification may occur. Gentrification refers to the transformation of the social, economic, cultural, physical and demographic features of a neighbourhood, and often leads to the displacement of long-term and socially marginalized residents (9). In a neighbourhood impacted by gentrification, property and rental values are inflated, pushing vulnerable populations to relocate.  However, there are ways to break the cycle of revitalization and displacement caused by gentrification. The City of Ottawa is incorporating public health concepts into urban growth strategies by creating ‘15-minute neighbourhoods’ (10). A 15-minute neighbourhood is one in which all (or most) daily needs can be accessed within a 15-minute walk from one’s home. The goal of a 15-minute neighbourhood is to reduce reliance on vehicles, increase social connections, and promote equity through improved access to daily needs (10). At the provincial level, Ontario has tried to combat income-based disparities in access to healthy built environments through inclusionary zoning regulations (11). Inclusionary zoning is a strategy to increase affordable housing in desirable neighbourhoods. Under an inclusionary zoning system, every new housing development must be mixed income, meaning that a range of income levels can afford to live in high-quality housing within updated neighbourhoods. Inclusionary zoning has shown some success in the United States, but there is concern that provincial actions will be ineffective at the municipal level. Under the current system, the power to enforce inclusionary zoning lies with municipal governments, that will need to implement bylaws and regulations surrounding the construction of affordable housing units (12). By leaving decisions on inclusionary zoning to municipalities, substantial changes are not guaranteed.  When we understand the magnitude of Ontario’s housing crisis, it is easy to support policy action, like inclusionary zoning. But, take a moment to consider your perspective if affordable housing was proposed in your own neighbourhood? As is too often the case, such a policy might be easy to support until you are personally affected. For residents living near areas allocated for affordable housing, the “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) phenomenon is both common and predictable. The NIMBY phenomenon refers to the opposition of new developments by residents when they believe the development will negatively impact their neighbourhood or property value. Classical examples of the NIMBY phenomenon include responses to safe injection sites and homeless shelters, but affordable housing is similarly affected (13). NIMBY responses are often founded in stereotypes and stigma and serve to perpetuate social inequities. One method governments and developers can use to fight the NIMBY phenomenon is to engage and inform residents throughout the planning process. Importantly, we can individually work against NIMBY-ism by discussing the value of diverse communities with family, friends, and neighbours and being leaders for social equity within our own neighbourhoods. As I sat at my desk in Toronto with the entire province under stay at home orders, I couldn’t help but appreciate how much I relied on my home and neighbourhood over the past year. But, for many Ontarians, hiding away at home has not been a refuge from the dangers of COVID-19. Improving access to healthy homes and neighbourhoods is a complex battle involving political priorities, revitalization and gentrification, and local sentiments. As we move forwards in the COVID-19 pandemic and into its aftermath, we must do more to ensure that “home” is a healthy environment for all Ontarians. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed