|

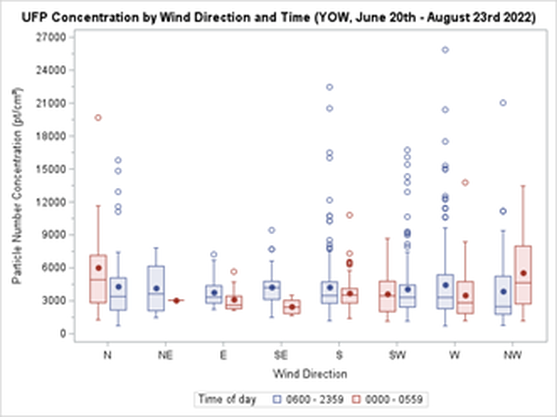

By Kieran Aston Researchers are aware that when it comes to outdoor airborne particulate matter, smaller types of particles are more harmful because they can enter the bloodstream when inhaled. Ultrafine particles (UFPs) are a type of air pollution particulate matter of nanoscale size (less than 100 nm in diameter). To put this into perspective, UFPs are about 1/1000 the diameter of a single strand of human hair. There is growing evidence that long term exposure to UFPs increases the risk of serious health outcomes including cancer, respiratory diseases, hypertension, and diabetes. As we learn more about the dangers of long-term UFP exposure, it becomes increasingly important to learn more about the different sources of UFP emissions and their health impacts. We need to look for ways to reduce exposure. In Canada, the primary source of UFPs is gasoline powered vehicles, but there are many other exposure sources such as diesel emissions and wood burning. That said, one crucial and understudied source of UFPs is aircraft use. Epidemiological studies found that airport related UFP emissions are substantial and may increase the risk of adverse birth outcomes. Since airport-related UFP emissions can spread significantly farther into the surrounding area than roadway-traffic emissions, they pose greater health risks and need to be specifically studied. By design, airport runways run parallel to the prevailing wind direction to create optimal landing and takeoff conditions. Unfortunately, residential areas downwind of airports are subjected to aviation emissions, particularly in cities with little variation in wind direction. During the summer of 2022, I helped collect data for a pilot study of Health Canada’s “Characterization of Aviation-Sourced Air Pollution (CASAP)” project to address UFPs research gaps. The project is led by Keith Van Ryswyk of Health Canada in collaboration with Dr. Paul Villeneuve of the CHAIM Center at Carleton University. The main component of the CASAP study will take place at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport, focusing on investigating the effect of airport-related emissions on the urban areas downwind of the airport. The project will also examine how new, more fuel-efficient landing technology can affect aviation emissions. The pilot study at the Ottawa International Airport was intended to provide an opportunity to fine-tune the methodology for data collection and analysis in preparation for the main study. We set up fixed-site monitoring equipment near a runway at the airport by installing a tripod-like contraption fitted with various instruments that continuously collecting data on pollutants, noise and weather. The site we chose is in line with the runway, and lies to the east of the airport, which is ideal for catching air pollution plumes from aircraft with the prevailing western winds in this area. I was responsible for ensuring that the monitors at the site had everything they needed to collect data on noise, black carbon, and particulate matter at the site. I also contributed to the analysis of the collected data. This meant making weekly visits to the site to replace depleted batteries, clean dirty filters, sync clocks, and offload data, battling mosquitoes and the keep the tech dry during the occasional freakish downpour. I also had to deal with any unexpected errors and mishaps with the devices, of which we had our fair share. A typical Monday for me started with driving out to Albion Road and heading down a more-than-a-little bumpy gravel road to the monitoring site. Once I made my way up a small hill to the monitoring setup, I connected my laptop to each of the devices, downloaded the data, cleared each device’s memory, and synced their clocks. Then, I replaced the devices that were out of battery with fully charged spares and replaced the dirty parts with clean ones. Finally, before leaving I thoroughly checked each instrument to make sure everything was in working order. Since flight data were not yet available at the time of my work on this study, my analysis of the collected data was limited to the effect that wind direction had on UFP concentrations. Some of my preliminary findings showed that UFP concentrations were in general higher during winds that put the monitoring site downwind of the airport (i.e., western winds) than when the monitoring site was upwind of the airport (i.e., during eastern winds), as shown in the graph below. In addition, when comparing UFP concentrations during hours of higher flight traffic (6:00 am – 11:59 pm) and lower flight traffic (12:00 am – 5:59 am), differences seen in both the variability and levels of UFP concentrations were much larger when the monitoring site was downwind of the airport than when it was upwind of the airport. For example, during western winds the standard deviation of recorded particle number concentrations (PNC) was 51.0% larger from 6:00 am – 11:59 pm than it was from 12:00 am – 5:59 am. Conversely, the difference in the standard deviation of PNC during eastern winds was more comparable, being 13.2% larger between 6:00 am – 11:59 pm than it was between 12:00 am – 5:59 am. The project’s next steps include comparing the collected data with flight data to be received from Nav Canada. Flight data allows for a more detailed analysis, and we hope that such an analysis can serve to better inform our methodology for the main portion of the study at Toronto’s Pearson Airport. Our pilot project was the first to collect data on UFPs from aircraft, and in time, we hope to assess whether these exposures impact the health of residents.

0 Comments

Angel Xing, CHAIM Centre Communications and Strategy Intern "There are so many barriers that queer and trans people face in getting access to health, so to say that the healthcare system is working well isn't right," says Dr. Julia Sinclair-Palm, a sociology professor at Carleton University.

Over the summer, the CHAIM Centre released its first CHAIM Chats series discussing queer and trans experiences in Canada's health system. The three episodes focus on specific barriers faced by the trans community in accessing healthcare. A 2021 article published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal found that LGBTQ+ communities still experience health inequities. Trans and non-binary people report that they often experience unmet needs or delays in receiving care. According to Dr. Sinclair-Palm, one barrier to health is the expectation for trans patients to align their gender presentation with the binary. "Medical professionals want a singular story about their transness," she says. "But it excludes non-binary, genderqueer and folks who don't present their gender in a binary way." Dr. Sinclair-Palm says trans patients are often expected to prove that they are trans to their healthcare professional to receive the care they need. "Trans folk are smart and good at navigating those terrible health systems. They've learned that they have to tell a particular story," they say. "But there's no singular queer or trans experience. There is no singular way to be trans, and when we other or cast trans folks as 'different,' we limit the understanding of the complexities of their lives," Dr. Sinclair-Palm says. Christian Wright, Rainbow Ottawa Student Experience (ROSE)'s lead coordinator, adds that the trans community is frequently mistreated in healthcare. They can be misgendered, asked inappropriate questions, called the wrong name and experience stereotypical assumptions. "People are afraid of going into these environments on top of the fact that accessing trans-specific healthcare is an incredibly frustrating and long process," Wright says. Another significant barrier to healthcare is the wait time. "Just to get an intake appointment at the premiere trans healthcare providing place in Ottawa, Centretown Community Health Center, is a two-year waitlist," Wright says. Then there is the wait time for actually receiving HRT or surgery. "Once they enter the door, there's another host of barriers," Dr. Sinclair-Palm says. "If they're seen as 'too mentally unstable,' they aren't granted access to the care they want. They're told they need to address those other issues when often, someone might be depressed or struggling because of the discrimination and violence they face." Florence Ashley, a transfeminine bioethicist and jurist, says that the healthcare system does not support the trans community. They researched how medical professionals often take the authority in determining if their patients are trans and if they need hormone replacement therapy (HRT) independent of their patient's wishes. "While science can be used to afford some degree of gender affirmation, it was also just as often used to limit it and expand medical power," they say. "The experts position themselves and accept their roles as authorities in accessing the child's gender and who is really trans." Ashley said they noticed in decisions before the court about parental behaviour towards trans youth that the medical professionals speak on behalf of the child. "They were the ones positioned as the spokesperson for the child to relate the 'true' views of the child," they say. However, when speaking for the child, Ashley says the experts would use ambiguous terms like "based on the child's feelings" so they can draw conclusions themselves. "Being trans is something that shouldn't be within the sphere of authority of doctors," Ashley says. "It's not their business in the first place to determine who is trans and who isn't." "It's harmful because it challenges trans people's fundamental self-knowledge about who they are." Wright says the authority of medicine in someone's trans identity also relates to transmedicalism, the idea that being transgender means medically transitioning to resolve gender dysphoria, which is psychological distress due to a mismatch between the gender assigned at birth and gender identity. Wright says, fortunately, the model of gender-affirming care is growing. Ashley adds that an Informed Consent Model (ICM) decenters clinical assessment, focusing on the client which removes the requirement to prove their gender identity to receive care. According to the Institute of Gender and Health, the ICM would does not evaluate if a person is trans; instead, it focuses on the decision-making process and ensuring that the patient understands the risks and benefits of HRT. Unfortunately, Ashley says ICM is limited by a lack of time. "We're in a consumerist medical system where doctors rarely get to have more than 15 to 30 minutes with you," they say. It is difficult to deeply discuss decision-making in a short session. Wright says this can be improved if healthcare professionals at the first access point, like family doctors, are more educated about trans health. Learning about trans health shouldn't be an additional and separate piece from cisgender health. "We need doctors who are preparing to be care providers and family physicians to be educated about HRT and options for surgery referrals," they say. "There need to be more resources put into creating a system which allows trans people to participate as fully as cis people do, from navigation to advocacy to support." Angel Xing, CHAIM Centre Communications and Strategy Intern  Three CHAIM Centre Affiliates shared their experiences as Asian researchers for Asian Heritage Month in May, discussing social and cultural health inequities, particularly in mental health. Dr. Melissa Chee, an assistant professor in Carleton's Neuroscience department and principal investigator at The Chee Lab, said she started reflecting more on how her Southeast Asian identity affects her professional career when the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement sparked discussions about systemic racism. "It's still a discovery process for me," she said. "I know that lately I've been more aware, and I sometimes pause to ask; am I not part of that, or am I part of that because I'm Asian?" Asians are often treated as the "model minority," a stereotype that characterizes Asians as academically and economically successful compared to other minority groups. According to an article by NPR, this undermines anti-Asian hate and creates a racial divide. Dr. Chee commented on the impact of this stereotype. "Asian women are actually underrepresented in science, and I feel I need to succeed in my role so others will continue to have the same opportunity," she said. Ajani Asokumar, who identifies as Tamil and is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Neuroscience at Carleton, agreed. "It made me really nervous because I have these expectations and pressures on me that I have to fulfill," she said, adding that sometimes she felt like she was being treated differently in academic and social settings. "You can detect it in the comments people make." In addition to the pressures, Asokumar also pointed out that Asian immigrant families don't often discuss stress and mental health, both heavily stigmatized topics. "In the Asian cultures typically, mental ill health is looked upon as almost shameful, a reflection of laziness," said Dr. Zul Merali, former scientific director of the University of Ottawa's Institute of Mental Health Research. Dr. Merali identifies with the South Asian community. "But mental illness is an illness like any other," he said. "It is not something you need to blame yourself for." Unfortunately, the pressure from Asian stereotypes combined with cultural mental health stigmas makes the Asian community more vulnerable to poor mental health. In 2016, CAMH reported that Chinese and South Asian patients had more severe mental illnesses when they were admitted to the hospital. Another issue the CAMH report identifies is that there is limited data on Chinese and South Asian patients in mental health research and general health research. Dr. Chee and Asokumar said an issue lies in the "Asian" categorization. "The Asian community is really diverse in Canada," Dr. Chee said. Besides different ethnicities and cultures, variables also include time spent in Canada and language barriers. "The experiences of someone new to Canada are very different from my experiences. I've been here my whole life." Asokumar added that mental health help is often only designed for Western people and feels alienating because the professionals don't have the same cultural understanding. "The help that's given is so general," she said. "We need better access to people who are better suited to help our needs." "When you present an opportunity, it might not be accessible to everyone equally." Dr. Merali said there are also great challenges in getting admission and treatment into the healthcare system, particularly for mental health, because the system is under-resourced. He said this affects all marginalized groups, especially because support like psychological counselling often requires private insurance. "All marginalized populations pay the price," he said. Since people from these communities cannot access mental health resources as easily, Dr. Merali said they are underrepresented in collected data for mental health studies. That said, Asokumar said she does feel like there are more people of colour in her program than there were in 2013 when she first came to Ottawa. She said there had been significant changes compared to when she was one of the few people of colour in her program. "I'm seeing more people who look like me, so it's a very positive thing that's happening," she said.

But she said she still sees mostly white men in authority positions. "I think more needs to be done. I do want to see more action," Asokumar said. Dr. Chee agreed there should be an increase in the diversity of people who sit on committees. "It's always on the back of your mind whether you were included because you're the token minority. Was I included because I am a minority and a woman? Or was I included because of my ability or expertise?" "We don't know whether our identity has hindered our ability to accelerate in our field," Dr. Chee said. "We think that we are here because we earned and deserve it, but how do we know that we didn't deserve more?" "We need more research. We need information and advocacy." By Lilo Noort, CHAIM Centre Communications Intern A One Health approach to the health issues that face the planet today requires collaborations across multiple sectors and disciplines locally, nationally, and globally. One Health works at the intersection of human and animal health, with the natural and built environments contributing to and transforming this relationship. The 2022 One Health Challenge concluded in March, when student groups presented their novel solutions to the challenge, they were given to create an intervention that promotes the public health benefits of enjoying the use of greenspaces in urban areas, while balancing the potential negative impacts on ecological health and biodiversity. A group of expert judges from different sectors deliberated over each solution. And following considerable discussion, they selected the creators of “Green Days,” for the top prize in the competition. This interdisciplinary team was made up of undergraduate students Malik Sylla (Computer Science), Veronica Yung (Interactive Multimedia and Design), Erika Uzoegwu (Health Sciences), and Frank Li (Engineering Physics) who were mentored by graduate student Sebastian Steven. “We knew we wanted to focus on green spaces and accessibility, and that idea evolved into our final template surrounding children and school children in urban centers. The entire aim of the project is to bridge the gap between green spaces and low-income children, because we know that these kids often experience a lack of green space access,” said Malik Sylla.

“The program is all about giving these children access to green spaces, and professionals who can teach them more about it,” Frank Li continues. The team discussed how they hoped that their innovation will help to connect young people to nature at an early age. They stressed the importance that green spaces can have on one's mental wellbeing, and how access to these spaces can improve the lives of children. “It was not our first idea at all, and we actually had to work on a few ideas before we had that aha moment.” “One of the most important things was looking at the gaps in the currently existing programs,” said Veronica Yung. She explains how while in school, she was only every shown a handful of career paths to consider. “Showing kids that there are options outside of what they show you in high school, was important to us,” she explains. “I feel like if kids exposed to opportunities to get outside the classroom and look at the world differently, they can make better choices later in life.” Green Days was a labor of love. The team explained how their combined talents, in a variety of fields, offered a unique advantage for completing the challenge successfully. “Health is more than just the choice you make,” said Erika Uzoegwu. She expressed how having an interdisciplinary approach to research is crucial for a project like this. Erika went on to describe how health is affected by “the choices that are like provided to you and that you have access to.” Uzoegwu outlines how one of the team’s biggest goals was to use their collective expertise to help uplift others. Their collective efforts to create a health innovation, has a goal of changing the lives of children from underfunded communities. “I heard a Mohamed Ali quote once that said, ‘service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth,’ which I think is really powerful in the One Health Context,” Sylla said. He explained how the team’s project developed over discussions about growing up in urban centers in North America. “It was important for us to look around and see the things we experienced as kids, the challenges we faced and how they can be improved,” he concluded. Moving forward the team recently presented “Green Days” at Carleton’s annual Life Sciences Day 5.0 on May 10, 2022. In line with the 2022 OHC, this year’s conference topic was surrounding healthy communities and the team had the chance to show case their intervention to many academic, government, and industry attendees. A long-term goal of the Green Days project is to expand across the country and help connect inner-city children to nature and environmental education. “Our generation is the future, and we have the ability to change the world,” Sylla said “we want to use our platform and the privilege we have to make a change for these kids, so they can continue to change the world for the better.” |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed