|

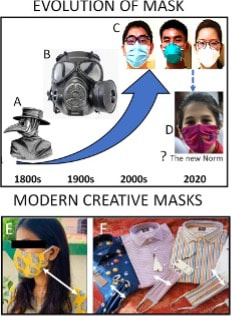

By Emily Tippins, Carleton Graduate Student Face masks have been a predominant symbol of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, mask mandates and mandates in general have been—and continue to be—quite divisive. With conflicting political and scientific messaging about the virus, many individuals are left unsure about the science behind masking and if they should continue to be worn to protect their health and the health of others. Previous studies have speculated that culture plays a fundamental role in shaping people’s response and subsequent health behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Biddlestone et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021). It has become increasingly apparent that behavioural science is essential for understanding and addressing the decisions on whether to refuse or adhere to health guidelines, as well as the influential role that cultural perspectives and political messaging have on these behaviours.  Historically, face masks have played an important role in protecting against the spread of infection (Bakshi et al., 2021). Masks were first aimed to stop bad smells until the 1700s when their medical functions became known. The “miasmatic” theory of disease hypothesized that most diseases were caused by inhaling a “miasma,” thought to be infected air through exposure to corpses and the exhalations of infected individuals (Halliday, 2001). As developments in the field of microbiology were made during the 1800s, miasmatic theory was disproved, and the mask began to transform from the iconic bird-beak masks (see Figure 1; mask A) which were filled with herbal materials thought to keep off the plague, to be more suitable to healthcare needs (see Figure 1; mask C; Lynteris, 2018). As health risks associated with asbestos inhalation became apparent and the risk of the inhalation of toxic dust was identified among mining and construction workers, recommendations were put in place to use masks in workplaces where exposure to harmful chemicals occurs (Goh et al., 2020). Presently, medical technology has advanced, and a large variety of face masks have been developed, many of which are being used by the general population for protection against COVID-19. However, even with the variety of masks available, the data is still unclear on how well they work or when to use them. Earlier this year, a Cochrane review was published suggesting that face masks don’t work in community settings. However, many experts criticized this review’s methodology and assumptions regarding infection transmission and warned that the conclusions are misleading. Contentious political discourse discrediting and discouraging the use of face masks has added to the confusion and decreased public adherence to this protective health behaviour around the world (Bakshi et al., 2021). One identified reason for the lack of compelling evidence on the efficacy of public mask wearing is the lack of controlled trials due to logistical and ethical reasons during the pandemic (Ju et al., 2021). Furthermore, it is thought that the primary route of transmission of COVID-19 is via respiratory particles; however, even this notion has been criticized. A systematic review sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that mask-wearing reduces transmissibility per contact by reducing transmission of infected respiratory particles (Chu et al., 2020). However, the amount of protection you receive from a mask depends on the quality of the mask and how well it fits. Thankfully, guidance from reputable sources like the Public Health Agency of Canada and the WHO have resources on proper COVID-19 mask use. Despite these available resources, many individuals still choose to not wear a mask in public spaces.  We now understand that face masks are most effective when 100% of the individuals in a public space are wearing one (Chu et al., 2020). Therefore, in order for protective face masks (in conjunction with other preventive health measures) to mitigate the transmission of COVID-19, they must be viewed as the standard acceptable behaviour by the general public in order to adopt and maintain this social norm (Bokemper et al., 2021). Research has shown that culture fundamentally shapes how people respond to crises like the COVID-19 pandemic (see Lu et al., 2021). It has also been found that collectivist cultures demonstrate greater adherence to social norms (see Tripathi & Leviatan, 2003). Collectivism encapsulates the tendency to be more concerned with the group’s needs, goals, and interests than with individualistic-oriented interests (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). It has been speculated that a sense of collectivism may improve individuals’ attitudes toward behaviours that involve personal discomfort, such as masking. Places with cultures that are considered to be more collectivist (e.g., Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea) contained the spread of COVID-19 more effectively than places with more individualist cultures (e.g., United States, Spain, and Italy; Biddlestone et al., 2020). Unfortunately, people in individualist cultures often prioritize their personal convenience or preference while ignoring the collective consequences of doing so. For example, although properly fitted masks effectively protect against COVID-19, they can be uncomfortable and create inconvenience. Thus, more community-minded thinking that aligns with collectivist cultural norms would need to be adopted in order to encourage mask-wearing in public settings.  Leadership is critical in adopting collectivist cultural norms (Lu et al., 2021). Unfortunately, the politicization of masks has led some individuals to not fully adopt masking due to political polarization. In fact, some report that choosing to wear a mask may be seen as making a political statement. Policy recommendations and the public acceptability of mask-wearing falls largely on the shoulders of government. As COVID-19 continues to spread, governments around the world debated on whether to recommend or mandate the use of masks in public. After the lifting of mandates in several countries, including Canada, responsibility to wear a mask shifted from a collective effort to an individual responsibility. However, Canada’s top doctors still recommend wearing a mask—even without mandates. The conflicting messaging between politicians and public health officials has become more confusing, leaving the decision to wear a mask in public up to individual comfort level. Unfortunately, people need guidance in times of uncertainty and that guidance cannot be nuanced (Capurro et al., 2021). Nuance will only create further confusion and increase potential opportunities for misinformation. As Canadians grow increasingly frustrated with the changing messaging and restrictions one message has become clear. We must now “learn to live with the virus.” But what exactly does living with COVID-19 entail? In order to move forward in a safe manner, there must be better efforts to bridge the gap between politics and science. Public health messaging must consider the motivational roots of health behaviours. In order to encourage individuals to continue to wear face masks without a mandated requirement to do so, strategies to increase collectivist behaviours must be considered. Understanding cultural differences and the power of social norms will provide insight into the current pandemic and help us prepare for future crises. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

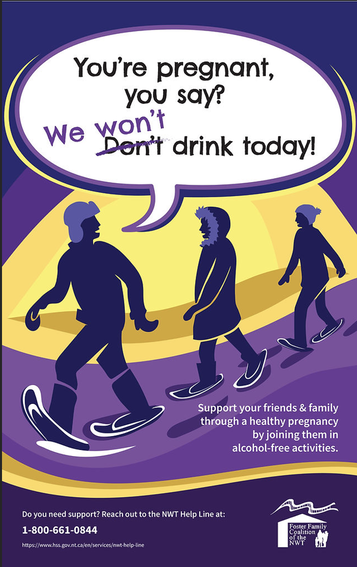

By Jade Alcantara, Carleton Graduate Student I clip my I.D. to a loop on my scrub pants and secure my name tag to my shirt, careful not to cover the acrylic words "NICU." Grabbing a pen, highlighter, and sharpie, I walk over to my patient assignment, where a solid incubator housing a tiny baby welcomes me. Seeing me approach, the nurse flips the patient's binder open for shift report. She skims through the mother's para and gravida that outlines her obstetric history before I interrupt her. "What's her name?" I ask "They haven't given her one yet." "No, the mom's." "Oh, Estella." "And the dad's?" I inquire "Hmm… I'm not sure. You can ask them when they visit tonight." She continues with para and gravida while my eyes skim the page, searching for an oversight. Sure enough, the dad's name is missing. And not just his name, everything. Not a single piece of paternal information is on this baby's kardex. No medical information, health history, anything. For all I know, my patient was miraculously conceived. As I scribble my colleague's updates onto my report sheet, the weight of this realization dawns on me. The document that my colleagues and I record critical updates and base our entire care plan on is missing a page worth of significant information—the father. I spend the rest of the shift bothered by this, cradling my patient, knowing only half her health history.  Fast forward one year later, and I'm still bothered. Perhaps the paternal health history wasn't considered relevant to my scope as a NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) nurse. I'd counter that by saying what concerns my patient concerns me. Rooted in cultural assumptions, women have historically, if not infamously, been deemed the "fetal environment" and treated as such—bearing all the physical, mental, and emotional pressures of fertility, childbearing, and child-rearing (Sharp et al., 2018). This seamless association between women and children set by society may have inadvertently sidelined men despite them being crucial players in family life. Family structures, dynamics, and roles have evolved considerably over the years to improve paternal involvement in family life. But we have yet to see paternal health fully appreciated as a critical contributor to fetal health and development. Just as a woman's health is passed on through her DNA, is the father's health not also passed on to future generations? The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) school of thought would say yes, and goes further still. English physician and epidemiologist David Barker hypothesized that early life nutrition, stress, and other environmental exposures set the stage for obesity, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease in later life (Gluckman et al., 2010). His theory redefined how the world perceived chronic diseases, conceiving a new field of science that would eventually become known as DOHaD. Barker proposed that adverse exposures had three-fold health outcomes—affecting the health of not just one person, one lifespan, but the health of their children and grandchildren (Edwards, 2019; Gluckman et al., 2010; Ryznar et al., 2021).  Recent DOHaD studies have explored the influence of lifestyle behaviours on gamete RNA and the resulting phenotypes observed among offspring (Gluckman et al., 2009; Ryznar et al., 2021). Gamete RNA has been demonstrated to produce offspring with a phenotype associated with their parent's lifestyle and health status (Ryznar et al., 2021). A study that fed mice a Western-like diet observed undesirable metabolic phenotypes among the pups that predisposed them to metabolic diseases and increased the risk of predisposing their future offspring to similar conditions (Grandjean et al., 2016). Likewise, a similar, more favourable observation was made among mice fed a healthy diet (Grandjean et al., 2016). This concept of transgenerational health outcomes, supported by numerous epigenetic studies in rodents, is evidenced in both mothers and fathers (Anway et al., 2006; Daxinger & Whitelaw, 2012; Manikkam et al., 2012; Manikkam et al., 2014; Skinner et al., 2013). Yet much of society, not excluding DOHaD academics, remain fixed on the false assumption that mothers' health is more influential toward fetal health outcomes and precursors of disease vulnerability in later life than fathers' health (Sharp et al., 2018). Operating under this false assumption of maternal "causal primacy" is a dangerous path (Sharp et al., 2018). Not only is it willful ignorance, but it also fuels outdated "cherchez la femme" misconceptions of family health and disease prevention that blame adverse health outcomes on the woman—presenting a misleading bias in research (Sharp et al., 2018). In their article, Sharp et al. (2018) yielded approximately forty paternal-related DOHaD articles compared to seven hundred maternal DOHaD articles. This ratio of research studies between moms and dads illustrates the depth to which these cultural assumptions have taken root and misguided research. The weight put on maternal causal primacy in public health promotion is equally staggering. I can't tell you the number of times I've walked into a public restroom greeted by the same poster. If you're reading this and are a young woman who grew up in Canada, I bet you know precisely which poster I'm talking about. A young lady, smiling and alone, cradling her belly with the words "alcohol and pregnancy don't mix." That poster's been around longer than I could drink. I'm not winding up to throw shade or criticize past health promotion strategies. The poster in question, after all, sparked awareness of fetal alcohol syndrome disorder (FASD) and was surely designed with the best of intentions and is an excellent example of simple but effective messaging. All the same, it's not the messaging nor the purpose I find off-putting but the visual messaging and its contribution to the maternal causal primacy issue. A young lady, smiling and alone. How burdensome. I wonder what the health promotion posters in men's washrooms look like… Why is society so set on making women the poster girls of family life? It's time we adjusted the spotlight and reframed the responsibility. We live in unprecedented times in which social media, technology, and globalization have demonstrated the ability to spread public service announcements and health misinformation like wildfire. We must take up this torch to ensure that the data circulating is credible and that media messaging supports not just men and women, but families. DOHaD studies have found that both men's and women's health influences gene expression and, by extension, healthy development and risk for disease in later life (Sharp et al., 2018). This evidence warrants the redistribution of prenatal health promotion to include both parents. We've all seen the classic "What to expect when you're expecting" book for women, and thankfully, more pregnancy books have expanded their target audience to include dads. We need to see equal representation of mothers and fathers throughout public health promotion strategies. A more recent promotional product for FASD awareness showed a group of people with the caption "Pregnant, you say? We won't drink today! – Support your friends and family through a healthy pregnancy by joining them in alcohol-free activities" (Foster Family Coalition of the Northwest Territories, n.d.). Wordier than the last, sure, but appreciably more meaningful, as supportive messaging goes. As illustrated by the clinical, research, and public health implications, society must champion the responsibility of promoting health for future generations. Family health should be a family effort—shouldered not just by one individual but by a village. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

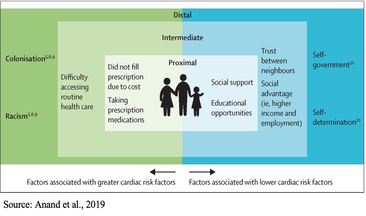

By Katy Cameron, Carleton Graduate Student Author’s Note: I would like to acknowledge that I am but one First Nations voice of many and recognize the diverse and unique experiences of Indigenous People across Turtle Island.  Source: Kamloops This Week, 2021 Source: Kamloops This Week, 2021 We are approaching two years since the initial discovery of the remains of 215 Indigenous children buried at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada. It came as shocking news for some and was a tragic confirmation for many Indigenous Peoples of what had long been suspected. For me, feelings of sadness and despair surfaced for my family and friends who experienced the Residential School system firsthand or were impacted by its legacy effects. Several of these schools were places that separated families, stripped children of their cultural traditions and knowledge, performed experimentations, and turned a blind eye to sexual and violent abuse. Only in the past decade or so has colonialization been acknowledged as a unique social determinant of health for Indigenous Peoples and efforts been made to understand its role in contributing to the disproportionate levels of chronic disease experienced by this population (Reading & Wien, 2009). But how exactly does colonization and its legacy impact the development of chronic disease, and why is this still a problem in 2023?  Source: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, 2022 Source: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, 2022 Diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, and cancer are all examples of chronic diseases in which environmental and/or individual factors promote the development of health conditions that are present for extended periods of time (Earle, 2011). It is commonly known that practicing healthy habits such as eating nutritious foods, getting enough sleep, and regularly exercising contributes to healthier outcomes and reduces the risk of developing chronic diseases and illnesses. Sounds easy enough, right? For many Indigenous people, however, the reality is that there are numerous social barriers to engaging in healthy behaviours. In the first-ever Indigenous Services Canada Annual Report to Parliament in 2020, Indigenous Peoples, especially First Nations living on-reserve, reported lower incomes, less education, reduced employment rates, worse housing conditions, and decreased life expectancy compared to non-Indigenous counterparts. They also reported greater likelihood of being in foster care and higher infant mortality rates, as well as higher rates of violence, victimization, and incarceration. This exemplifies the magnitude of the inequities experienced by this population, and it is understandable why Indigenous Peoples are at greater risk for developing disproportionate rates of disease, illness, and even deaths. Conversely, a study conducted by Anand et al. (2019) found that First Nations communities with higher incomes, better education, increased access to healthcare services, and robust social support mechanisms displayed fewer risk factors for cardiovascular disease compared to communities with overall lower socioeconomic status. Moreover, other research indicates that socioeconomic and lifestyle factors contribute to the high proportion of First Nations who suffer from diabetes (Halseth, 2019). These findings support the position that the social determinants of health play a significant role in contributing to the subsequent development of chronic disease amongst First Nations and other Indigenous groups.  So, how does colonization and its legacy effects tie into chronic health disparities? According to one article, there are proximal, intermediate, and distal social determinants at play. Proximal determinants are those that directly impact healthy behaviours (e.g., physical environment), intermediate determinants are institutional or system-specific (e.g., education level and health care accessibility), and distal determinants are the bigger-picture issues from which many of these factors stem, such as colonialism and racism. Colonialism has been defined as the exploitation, control, and settlement of one country by another (Blakemore, 2019). In Canada, this involved removing autonomy from Indigenous Peoples and using assimilation strategies such as Residential Schools, separating children and families through the Sixties Scoop, and continues today by disproportionately placing Indigenous children in the Child Welfare System (Hobson, 2022). For many Indigenous families, the proximal effects of these initiatives resulted in broken-family dynamics and unstable living situations, depression and overall poor mental health, a loss of sense of self, and substance use. Furthermore, intermediate effects such as a lack of access to, or affordability of, adequate treatment services for these outcomes have ultimately led to intergenerational traumas, and high rates of suicide (Bombay et al., 2014), and we are now seeing higher prevalence rates than ever of chronic diseases like diabetes amongst First Nations youth (Halseth, 2019). If we know that colonialism has shaped both the social determinants and direct health outcomes of Indigenous Peoples (i.e., increased chronic diseases), why do these issues continue to persist?  In 2015, the Canadian Government accepted the final report released by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which outlined 94 Calls to Action targeted at improving Indigenous health, education, and other domains. Although efforts have been made towards addressing these Calls, colonialism persists through current Westernized structural and governance frameworks, policies, and practices that continue to perpetuate the disadvantages and inequalities experienced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada (Blanchet Garneau et al., 2021; Czyzewski, 2011). Prime examples of this can be seen with policing issues, the overrepresentation of Indigenous People in the Canadian criminal justice system (Clarke, 2019), and insufficient culturally sensitive health educational programming, which can result in discrimination and harmful stereotyping (Blanchet Garneau et al., 2021). Increased collaboration and open communication between different levels of government and Indigenous leaders are needed to act on the chronic health disparities we know disproportionately affect Indigenous Peoples. Targeting the social determinants that impact this population, by increasing employment and educational opportunities and guaranteeing equitable access to basic necessities such as adequate healthcare and clean drinking water, is needed in order to ensure better health outcomes for future generations. As we are reminded of the horrific truths about the history of the Residential School system and the effects of colonialization through continued media reports of more unmarked graves, remember that the effects of colonialism are not a thing of the past. In fact, we still see the legacy effects on Indigenous health today, if we are willing to look. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

By Sebastian Steven, Carleton University Graduate  Living in downtown Ottawa means never being far from a demonstration. The nation’s capital is the ideal venue for protests against invasions or displays of solidarity for climate action and social justice. A different kind of demonstration, however, was organized here in early 2022. Stepping outside my apartment near Bank Street dropped me into the “Freedom Convoy.” The Convoy first labelled itself as a protest against a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for truckers crossing the border into the United States but shifted almost immediately into an unlawful occupation of Ottawa streets set on ending all COVID-19 vaccine mandates and removing public health restrictions. The Convoy occupation rallied against undeniably lifesaving measures. There have been significantly fewer deaths due to COVID-19 in individuals who have been vaccinated. Moreover, public health measures (PHMs) for masking, social distancing, and isolation of positive cases have reduced COVID-19 infection. Combined, vaccines and PHMs have spared many from both mild symptoms and severe months-long disabilities that could come from COVID-19 infection. Individuals with ties to and involvement in hate groups organized and participated in this Convoy. However, of interest to this post, some Convoy occupants were more focused on simply opposing PHMs. This subset of participants demonstrated a fundamental misunderstanding of science guiding the pandemic response in Canada during their displays of opposition. Despite aiming to highlight perceived issues with vaccine mandates and PHMs, occupants instead highlighted that some Canadians may not have strong enough knowledge of science and health. Jordan Klepper’s interview with occupants of Rideau St, for example, includes one unvaccinated man who was bewildered that his status means “[he] can’t go to the restaurants, can’t play hockey, and can’t go watch the [Ottawa Senators].” He seemingly views vaccination simply as a method to bar certain individuals of the population from public spaces without acknowledging the science informing these policies. Other knowledge gaps in science and health were seen in Convoy propaganda. Signs questioned scientists' motivations, discounted the value of PHMs, and drew unsupported concerns about deaths from surgeries delayed by COVID-19. These individuals displayed low health literacy during their participation in the Convoy. Health literacy is defined by the World Health Organization as: People’s knowledge, motivation, and competences to access, understand, and appraise health information in order to make judgments and take decisions in every-day life concerning health care, disease prevention, and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course. Equipping Canadians with skills in health literacy can enhance one’s ability to understand their health status and improve it. Health literacy is displayed, for example, when one can collect and understand information surrounding the risk of COVID-19 to then take steps to mitigate infection. The ability to do this, though, varies among Canadians. Estimates from 2008 show that 60% of Canadian adults are unable to obtain, understand, and act upon health information shared with them. This alarming statistic is more problematic with no national update to this estimate since 2008. Granted, the number of participants in the Convoy was minimal compared to the entire population of Canada. However, the occupation made it obvious that there are still Canadians who have not achieved sufficient health literacy. Convoy propaganda showed that low health literacy continues to be a significant problem in Canada into 2022. Some occupants who rallied against PHMs, for example, may not have the knowledge to take in the evidence showing that these measures increase safety for an entire population. The unvaccinated man interviewed by Klepper may not have been exposed to accessible health messaging describing that entering high-risk environments without being vaccinated puts himself in much higher danger of being infected with and dying from COVID-19. Shifting from a mindset that lacks concrete health and science-related knowledge to a more informed viewpoint would demonstrate improved health literacy. Health literacy, though, is not an issue of solely individual level factors. It is a social determinant of health (SDoH). This term refers to the unique living conditions one experiences that shape their health. SDoH are often influenced by systemic issues (e.g., socio-economic status, education level, etc.) that cause general societal inequities. Health literacy falls in line with this. Lower-income Canadians, for example, tend to have lower health literacy skills. A similar trend has been seen in Canadians with no post-secondary education. Individuals with little educational background are more likely to have insufficient health literacy skills. Children, even, receive most of their knowledge related to COVID-19 from parents, suggesting that one’s health literacy may be influenced by and sustained through generations. In total, research has demonstrated how engrained health literacy is as a SDoH. Importantly, gaps in health literacy have direct effects on the health of an individual and the population. Individuals who have both chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder and low health literacy skills, for example, tend to have a lower quality of life. Other general findings show that individuals with combined chronic illness and low health literacy skills have higher rates of mortality from their illness. These findings are especially troubling knowing that the proportion of older adults in the Canadian population will increase in the coming years. Improving national health literacy could therefore reduce the burden on the Canadian health care system for the care of chronic illnesses that will become increasingly prevalent in an aging population. Improving health literacy across a population could also empower individuals in subsequent pandemics to understand public health messaging and incorporate it into health behaviours that keep all members of society safe. Many existing definitions of health literacy do not adequately acknowledge the very real influence of the SDoH. As a result, interventions to improve health literacy may be too narrowly focused on individual factors. The Convoy shows, instead, that population-level interventions guided by the SDoH make more sense. The occupants did not exist solely within themselves but were members of diverse families, earners of varying incomes, and with varied educational backgrounds. These factors are large-scale SDoH that influence health literacy levels and overall health. This may be why previous attempts at improving health literacy in a one-on-one clinical setting have largely failed to make great impacts on health outcomes; issues influenced by large systemic factors cannot be fixed by small-scale individual level interventions. Community-based interventions have been suggested as a possible method by which to bolster skills in health literacy. Attempting to improve the health literacy skills of entire communities aligns with the knowledge that health literacy is a SDoH and addresses previously stated concerns. Research suggests that programs should be tailored to the unique SDoH of each community. This would require developing intervention tools that are specific to the community’s culture. This could include pairing health literacy skill workshops, for example, with programs that aim to improve other influential SDoH like education and income. Population-level interventions like these could have a much broader effect on the health of Canadians because they would inherently account for the large systemic influences that dictate skills in health literacy. Downtown Ottawa continues to be a stage to discuss current issues in Canadian society. Though the Freedom Convoy occupants may have felt they were putting on a performance solely to rally against pandemic-related issues, they were, in fact, bringing a different fundamental Canadian issue to the spotlight. The Convoy showed that we must improve the health literacy of Canadians. Doing so is imperative because health literacy is a SDoH with definite influence over the general health of individual Canadians. Health literacy must be addressed if we wish to improve the health of Canadians. Taking action on this issue could even prevent future disruptive occupations during public health crises. The exasperated residents of Ottawa and those occupying the city streets could both be helped by viewing such issues through the lens of health literacy. Though, I admit, this is a difficult mindset change to make, speaking as one of those exasperated Ottawa citizens living in the middle of the occupation. That being said, my background in health sciences has taught me that addressing issues at the systemic level is often the best way to bring about meaningful change. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course

|

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed