|

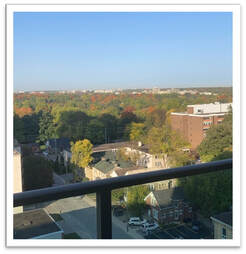

Claire Tizzard, Carleton University Graduate  London, Ontario. October, 2020 London, Ontario. October, 2020 The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we think about a lot of things including the way we travel, how we shop, and even where we live. Early on, as the pandemic containment measures were announced, it seemed that those who could were trading in their urban lives for the peace and tranquility of their rural cottages. Inspired, perhaps, by the wish to escape the higher transmission rates in urban centers but also the increasingly strict restrictions on public space. Those who longed for nature were encouraged to seek rural areas and homes with private backyard space in place of their urban apartments. Given that this is not an accessible option for most people, the role of urban development in the promotion of resilience and well-being has been brought into sharp focus. The thought of urban development might elicit images in our minds of new apartment buildings with large windows and rooftop patios, and while this is not the extent of urban development, it does make up an important part. The architectural features of our living space contribute to our mental health and wellbeing, particularly when we face restrictions on our ability to leave these spaces. The loss of daily routine, social gatherings, and the amalgamation of home and workspace have had a significant impact on mental health and wellbeing, all of which are compounded for those in densely packed urban areas.  A study conducted in Northern Italy, a region that experienced severe lockdown restrictions due to COVID-19, looked at the impact of features of built living spaces on university students found that living in small apartments, lacking a functional balcony, and having a poor view were each associated with moderate to severe depression symptoms (1). These living features are not uncommon as we experience a global trend of movement to urban centers where space is limited. To combat these negative psychological effects, people took to parks and local greenspace. A study that analyzed data from the Google Community Mobility Report found an increase in park visitation from February to May 2020, by over 100%, compared to the same time period the previous year, in Canada, Denmark, and the United Kingdom. Similar increases were found in Spain and Italy once the most strictest lockdown restrictions were lifted (2).  Time outdoors appears to be an important coping strategy. Nature provides an escape from confined living quarters and a time of relaxation to release the stress and anxiety felt most acutely by those in urban centers. Urban greenspaces are not only places to enjoy nature and physical activity but are also places to enjoy social connection. Community gardens and parks help foster social ties that can be maintained safely during social distancing measures to further reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness and foster resilience in a community. A survey of Tokyo residents explored the relationship between mental health scores, outdoor experience, and lifestyle factors to further understand their interaction amidst the increased psychological stress of the coronavirus pandemic. They found that greenspace use and view were both individually associated with higher life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem scores. Greenspace use and view were also both independently associated with lower loneliness, depression and anxiety scores (3). This supports the importance of greenspace in maintaining our mental health and wellbeing through periods of significant stress. However, greenspace is not equally accessible. Data from the Google Community Report found that park visitation and access were correlated with economic, cultural, and social dimensions. Higher socio-economic status communities experienced greater park access and visitation rates, while poverty and unemployment were correlated with reduced park access and visitation (2). Wealthier areas tend to have a greater diversity of species, higher tree cover, and are therefore, less susceptible to environmental changes (4). This inequality in greenspace access could compound the negative effects felt by disadvantaged populations due to COVID-19. Recognizing these data is important in our understanding of the impact of urban development on our wellbeing, especially as we prepare for future pandemics where quarantine measures may again be necessary for preliminary containment. Architectural design should include consideration of living features that have been found to be correlated with positive mental health and wellbeing such as a livable balcony, increased natural lighting, and larger and more functional space, all of which are a function of access to resources and socio-economic status. In addition, urban nature protection and development should be a priority as they have been shown to protect mental wellbeing and foster resilience in communities. Focus should also be brought to increasing equity in the distribution of urban nature development to benefit lower socio-economic communities who are at an increased risk of experiencing negative impacts to wellbeing.  The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we think about a lot of things, including how we appreciate urban greenspaces. They are no longer simply spaces that we enjoy individually, but have become crucial to maintaining our mental health and wellbeing. Urban greenspaces are places for physical activity, stress relief, and community interaction, all of which are key to combatting feelings of loneliness and isolation during lockdown restrictions. As we prepare for future pandemics, urban development that prioritizes greenspace is fundamental to fostering resilience in those who live in urban centers. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed