|

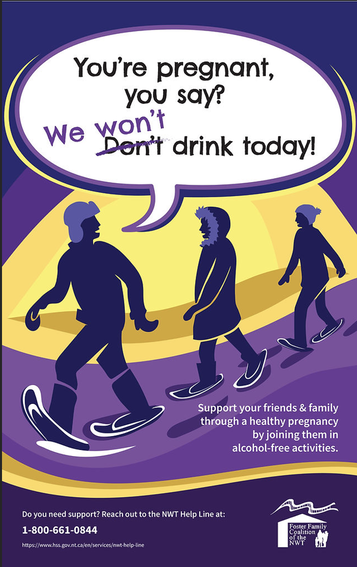

By Jade Alcantara, Carleton Graduate Student I clip my I.D. to a loop on my scrub pants and secure my name tag to my shirt, careful not to cover the acrylic words "NICU." Grabbing a pen, highlighter, and sharpie, I walk over to my patient assignment, where a solid incubator housing a tiny baby welcomes me. Seeing me approach, the nurse flips the patient's binder open for shift report. She skims through the mother's para and gravida that outlines her obstetric history before I interrupt her. "What's her name?" I ask "They haven't given her one yet." "No, the mom's." "Oh, Estella." "And the dad's?" I inquire "Hmm… I'm not sure. You can ask them when they visit tonight." She continues with para and gravida while my eyes skim the page, searching for an oversight. Sure enough, the dad's name is missing. And not just his name, everything. Not a single piece of paternal information is on this baby's kardex. No medical information, health history, anything. For all I know, my patient was miraculously conceived. As I scribble my colleague's updates onto my report sheet, the weight of this realization dawns on me. The document that my colleagues and I record critical updates and base our entire care plan on is missing a page worth of significant information—the father. I spend the rest of the shift bothered by this, cradling my patient, knowing only half her health history.  Fast forward one year later, and I'm still bothered. Perhaps the paternal health history wasn't considered relevant to my scope as a NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) nurse. I'd counter that by saying what concerns my patient concerns me. Rooted in cultural assumptions, women have historically, if not infamously, been deemed the "fetal environment" and treated as such—bearing all the physical, mental, and emotional pressures of fertility, childbearing, and child-rearing (Sharp et al., 2018). This seamless association between women and children set by society may have inadvertently sidelined men despite them being crucial players in family life. Family structures, dynamics, and roles have evolved considerably over the years to improve paternal involvement in family life. But we have yet to see paternal health fully appreciated as a critical contributor to fetal health and development. Just as a woman's health is passed on through her DNA, is the father's health not also passed on to future generations? The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) school of thought would say yes, and goes further still. English physician and epidemiologist David Barker hypothesized that early life nutrition, stress, and other environmental exposures set the stage for obesity, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease in later life (Gluckman et al., 2010). His theory redefined how the world perceived chronic diseases, conceiving a new field of science that would eventually become known as DOHaD. Barker proposed that adverse exposures had three-fold health outcomes—affecting the health of not just one person, one lifespan, but the health of their children and grandchildren (Edwards, 2019; Gluckman et al., 2010; Ryznar et al., 2021).  Recent DOHaD studies have explored the influence of lifestyle behaviours on gamete RNA and the resulting phenotypes observed among offspring (Gluckman et al., 2009; Ryznar et al., 2021). Gamete RNA has been demonstrated to produce offspring with a phenotype associated with their parent's lifestyle and health status (Ryznar et al., 2021). A study that fed mice a Western-like diet observed undesirable metabolic phenotypes among the pups that predisposed them to metabolic diseases and increased the risk of predisposing their future offspring to similar conditions (Grandjean et al., 2016). Likewise, a similar, more favourable observation was made among mice fed a healthy diet (Grandjean et al., 2016). This concept of transgenerational health outcomes, supported by numerous epigenetic studies in rodents, is evidenced in both mothers and fathers (Anway et al., 2006; Daxinger & Whitelaw, 2012; Manikkam et al., 2012; Manikkam et al., 2014; Skinner et al., 2013). Yet much of society, not excluding DOHaD academics, remain fixed on the false assumption that mothers' health is more influential toward fetal health outcomes and precursors of disease vulnerability in later life than fathers' health (Sharp et al., 2018). Operating under this false assumption of maternal "causal primacy" is a dangerous path (Sharp et al., 2018). Not only is it willful ignorance, but it also fuels outdated "cherchez la femme" misconceptions of family health and disease prevention that blame adverse health outcomes on the woman—presenting a misleading bias in research (Sharp et al., 2018). In their article, Sharp et al. (2018) yielded approximately forty paternal-related DOHaD articles compared to seven hundred maternal DOHaD articles. This ratio of research studies between moms and dads illustrates the depth to which these cultural assumptions have taken root and misguided research. The weight put on maternal causal primacy in public health promotion is equally staggering. I can't tell you the number of times I've walked into a public restroom greeted by the same poster. If you're reading this and are a young woman who grew up in Canada, I bet you know precisely which poster I'm talking about. A young lady, smiling and alone, cradling her belly with the words "alcohol and pregnancy don't mix." That poster's been around longer than I could drink. I'm not winding up to throw shade or criticize past health promotion strategies. The poster in question, after all, sparked awareness of fetal alcohol syndrome disorder (FASD) and was surely designed with the best of intentions and is an excellent example of simple but effective messaging. All the same, it's not the messaging nor the purpose I find off-putting but the visual messaging and its contribution to the maternal causal primacy issue. A young lady, smiling and alone. How burdensome. I wonder what the health promotion posters in men's washrooms look like… Why is society so set on making women the poster girls of family life? It's time we adjusted the spotlight and reframed the responsibility. We live in unprecedented times in which social media, technology, and globalization have demonstrated the ability to spread public service announcements and health misinformation like wildfire. We must take up this torch to ensure that the data circulating is credible and that media messaging supports not just men and women, but families. DOHaD studies have found that both men's and women's health influences gene expression and, by extension, healthy development and risk for disease in later life (Sharp et al., 2018). This evidence warrants the redistribution of prenatal health promotion to include both parents. We've all seen the classic "What to expect when you're expecting" book for women, and thankfully, more pregnancy books have expanded their target audience to include dads. We need to see equal representation of mothers and fathers throughout public health promotion strategies. A more recent promotional product for FASD awareness showed a group of people with the caption "Pregnant, you say? We won't drink today! – Support your friends and family through a healthy pregnancy by joining them in alcohol-free activities" (Foster Family Coalition of the Northwest Territories, n.d.). Wordier than the last, sure, but appreciably more meaningful, as supportive messaging goes. As illustrated by the clinical, research, and public health implications, society must champion the responsibility of promoting health for future generations. Family health should be a family effort—shouldered not just by one individual but by a village. References:

This blog was originally written as part of the HLTH5402 course.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed